U bent hier

Toegankelijkheid

Discover the Singing Nuns Who Have Turned Medieval Latin Hymns into Modern Hits

We now live, as one often hears, in an age of few musical superstars, but towering ones. The popular culture of the twenty-twenties can, at times, seem to be contained entirely within the person of Taylor Swift — at least when the media magnet that is Beyoncé takes a breather. But look past them, if you can, and you’ll find formidable musical phenomena in the unlikeliest of places. Take the Poor Clares of Arundel, a group of singing nuns from Sussex who, during the COVID-19 pandemic, “smashed all chart records to become not only the highest-charting nuns in history, but also the UK’s best-selling classical artist debut,” reports Classic FM’s Maddy Shaw Roberts.

“Music is at the heart of the nuns’ worship,” writes the Guardian’s Joanna Moorhead, but the idea of putting out an album “came about initially as a bit of a joke.” Not long after receiving a visit from a curious music producer, the singing Poor Clares — skilled and unskilled alike — found themselves in a proper recording studio, laying down tracks.

(adsbygoogle = window.adsbygoogle || []).push({}); . -->Roberts describes the resulting debut Light for the World as “a collection of Latin hymns produced for a twenty-first century audience, bringing calm and beauty during a time when so many were separated from their loved ones.” Just a few weeks ago, they released its follow-up May Peace I Give You, the video for whose title track appears at the top of the post.

May Peace I Give You comes from Decca Records, a label famous in part for their rejection, in 1962, of a scruffy rock-and-roll band called the Beatles. Presumably determined not to make the same mistake twice, they’ve since taken chances on all manner of acts, starting with the Rolling Stones; over the decades, they’ve reached beyond the well-trodden spaces in popular and classical music. The success of the Poor Clares goes to show that this practice continues to pay off, and that — like the popular Gregorian chant and gospel booms of decades past — venerable holy music retains its resonance even in our trend-driven, not-especially-religious age. And as the promotion of their new Abbey Road-recorded album proves, even for the monastically disciplined, some temptations are irresistible.

via Classic FM

Related content:

Manuscript Reveals How Medieval Nun, Joan of Leeds, Faked Her Own Death to Escape the Convent

Based in Seoul, Colin Marshall writes and broadcasts on cities, language, and culture. His projects include the Substack newsletter Books on Cities, the book The Stateless City: a Walk through 21st-Century Los Angeles and the video series The City in Cinema. Follow him on Twitter at @colinmarshall or on Facebook.

Watch Stalker, Andrei Tarkovsky’s Mind-Bending Masterpiece Free Online

“I feel like every single frame of the film is burned into my retina,” said Oscar-winning actress Cate Blanchett about the movie Stalker (1979). “I hadn’t seen anything like it before and I haven’t really seen anything like it since.

Andrei Tarkovsky’s final film in the USSR seems like an unlikely movie to have a devoted, almost cultish, following. It is a dense, multivalent, maddeningly elusive work that has little of the narrative pay-offs of a Hollywood movie. Yet the film is so slippery and so seemingly pliable to an endless number of interpretations that it requires multiple viewings. “I’ve seen Stalker more times than any film except The Great Escape,” wrote novelist and critic Geoff Dyer,” and it’s never quite as I remember. Like the Zone, it’s always changing.”

(adsbygoogle = window.adsbygoogle || []).push({}); . -->The movie’s story is simple: a guide, called here a Stalker, takes a celebrated writer and a scientist from a rotting industrial cityscape into a verdant area called The Zone, the site of some undefined calamity which has been cordoned off by rings of razor wire and armed guards. There, one supposedly can have their deepest, darkest desires fulfilled. Yet even if you manage to give the guards a slip, there are still countless subtle traps laid by whatever sentient intelligence that controls the Zone. Rationality is of no help here. One can only progress along a meandering path that can only be followed by intuition.

The Stalker, with his shaved head and a perpetually haunted expression on his face, is a sort of holy fool; a man who is both addicted to the strange energy of the Zone and bound to help his fellow man. His clients’ motives, however, are far less altruistic. Once deep in the room, the three engage in a series of philosophical arguments that quickly turns personal.

The movie’s power, however, is not found in traditional dramatics. Instead it’s a cumulative effect of Tarkovsky’s hypnotic pace, his philosophical commentary and perhaps most of all his imagery. Shot with smudgy, almost completely desaturated colors, the world outside the Zone seems to be a grim, dismal place – as if Tarkovsky were trying to evoke the industrial hellscape of Eraserhead by way of Samuel Beckett. (Stalker was in fact shot in an industrial wasteland outside of Tallinn, Estonia, down river from a chemical plant. Exposure to that plant’s runoff might very well have caused the filmmaker’s death.) Inside the Zone, however, the surroundings are lush and colorful, filled with glimpses of inexplicable wonder and beauty.

Stalker screenwriter Arkady Strugatsky once said that the movie was not “a science fiction screenplay but a parable.” The question is, a parable of what? Religious faith? Art? The cinema itself? Reams of paper have been devoted to this question and I’m not offering any theories. Tarkovsky himself, in his book Sculpting Time, wrote “People have often asked me what The Zone is, and what it symbolizes…The Zone doesn’t symbolize anything, any more than anything else does in my films: the zone is a zone, it’s life.”

Of course, that explanation does little to explain the film’s startling, utterly cryptic final minutes.

Above, you can watch the film online, thanks to Mosfilm. You can also find other Tarkovsky films in the Relateds below.

Related Content:

Andrei Tarkovsky’s Very First Films: Three Student Films, 1956–1960

Andrei Tarkovsky Answers the Essential Questions: What is Art & the Meaning of Life?

Jonathan Crow is a Los Angeles-based writer and filmmaker whose work has appeared in Yahoo!, The Hollywood Reporter, and other publications. You can follow him at @jonccrow. And check out his blog Veeptopus, featuring lots of pictures of vice presidents with octopuses on their heads. The Veeptopus store is here.

Beautifully-Preserved Frescoes with Figures from the Trojan War Discovered in a Lavish Pompeii Home

Image via Pompeii Archaeological Park

Imagine visiting the home of a prominent, wealthy figure, and at the evening’s end finding yourself in a room dedicated to late-night entertaining, painted entirely black except for a few scenes from antiquity. Perhaps this wouldn’t sound entirely implausible in, say, twenty-first century Silicon Valley. But such places also existed in antiquity itself: or at least one of them did, as recently discovered in Pompeii. Preserved for nearly two millennia now by the ash of Mount Vesuvius, the ruins of that city give us the clearest and most detailed archaeological insights we have into life at the height of the Roman Empire — but even today, a third of the site has yet to be excavated.

That archaeological dig continues apace, and its latest discovery — more recent than the Pompeiian “snack bar” and “pizza” previously featured here on Open Culture — is “a spectacular banqueting room with elegant black walls, decorated with mythological characters and subjects inspired by the Trojan War,” including such mythological characters as Helen, Paris, Cassandra, and Apollo.

(adsbygoogle = window.adsbygoogle || []).push({}); . -->“It provided a refined setting for entertainment during convivial moments, whether banquets or conversations, with the clear aim of pursuing an elegant lifestyle, reflected by the size of the space, the presence of frescoes and mosaics dating to the Third Style.”

Frescoes in that Roman Third Style, explains Hyperallergic’s Rhea Nayyar, feature “small, finely painted figures and subjects that seem to float within monochromatic fields,” designed “to mimic framed works of art or altars through illusions resembling carved beams, shaded pillars, and shining candelabras — all of which were painted on flat walls.”

The color of those walls, in this case, seems to have been chosen to hide the carbon deposits left by oil lamps burning all night long. As reported by BBC Science News, the commissioner of this room, and indeed of the lavish house in which it’s located, may have been Aulus Rustius Verus, a “super-rich” local politician who — assuming decisive archaeological evidence emerges in his favor — also knew how to party.

via Hyperallergic

Related content:

A Newly-Discovered Fresco in Pompeii Reveals a Precursor to Pizza

Take a High Def, Guided Tour of Pompeii

Archaeologists Discover an Ancient Roman Snack Bar in the Ruins of Pompeii

Watch the Destruction of Pompeii by Mount Vesuvius, Re-Created with Computer Animation (79 AD)

Pompeii Rebuilt: A Tour of the Ancient City Before It Was Entombed by Mount Vesuvius

Based in Seoul, Colin Marshall writes and broadcasts on cities, language, and culture. His projects include the Substack newsletter Books on Cities, the book The Stateless City: a Walk through 21st-Century Los Angeles and the video series The City in Cinema. Follow him on Twitter at @colinmarshall or on Facebook.

Creating Your Own Custom AI Assistants Using OpenAI GPTs: A Free Course from Vanderbilt University

Last fall, OpenAI started letting users create custom versions of ChatGPT–ones that would let people create AI assistants to complete tasks in their personal or professional lives. In the months that followed, some users created AI apps that could generate recipes and meals. Others developed GPTs to create logos for their businesses. You get the picture.

If you’re interested in developing your own AI assistant, Vanderbilt computer science professor Jules White has released a free online course called “OpenAI GPTs: Creating Your Own Custom AI Assistants.” On average, the course should take seven hours to complete.

Here’s how he frames the course:

This cutting-edge course will guide you through the exciting journey of creating and deploying custom GPTs that cater to diverse industries and applications. Imagine having a virtual assistant that can tackle complex legal document analysis, streamline supply chain logistics, or even assist in scientific research and hypothesis generation. The possibilities are endless! Throughout the course, you’ll delve into the intricacies of building GPTs that can use your documents to answer questions, patterns to create amazing human and AI interaction, and methods for customizing the tone of your GPTs. You’ll learn how to design and implement rigorous testing scenarios to ensure your AI assistant’s accuracy, reliability, and human-like communication abilities. Prepare to be amazed as you explore real-world examples and case studies, such as:

1. GPT for Personalized Learning and Education: Craft a virtual tutor that adapts its teaching approach based on each student’s learning style, providing personalized lesson plans, interactive exercises, and real-time feedback, transforming the educational landscape.

2. Culinary GPT: Your Personal Recipe Vault and Meal Planning Maestro. Step into a world where your culinary creations come to life with the help of an AI assistant that knows your recipes like the back of its hand. The Culinary GPT is a custom-built language model designed to revolutionize your kitchen experience, serving as a personal recipe vault and meal planning and shopping maestro.

3. GPT for Travel and Business Expense Management: A GPT that can assist with all aspects of travel planning and business expense management. It could help users book flights, hotels, and transportation while adhering to company policies and budgets. Additionally, it could streamline expense reporting and reimbursement processes, ensuring compliance and accuracy.

4. GPT for Marketing and Advertising Campaign Management: Leverage the power of custom GPTs to analyze consumer data, market trends, and campaign performance, generating targeted marketing strategies, personalized messaging, and optimizing ad placement for maximum engagement and return on investment.

You can sign up for the course at no cost here. Or, alternatively, you can elect to pay $49 and receive a certificate at the end.

As a side note, Jules White (the professor) also designed another course previously featured here on OC. It focuses on prompt engineering for ChatPGPT.

Related Content

A New Course Teaches You How to Tap the Powers of ChatGPT and Put It to Work for You

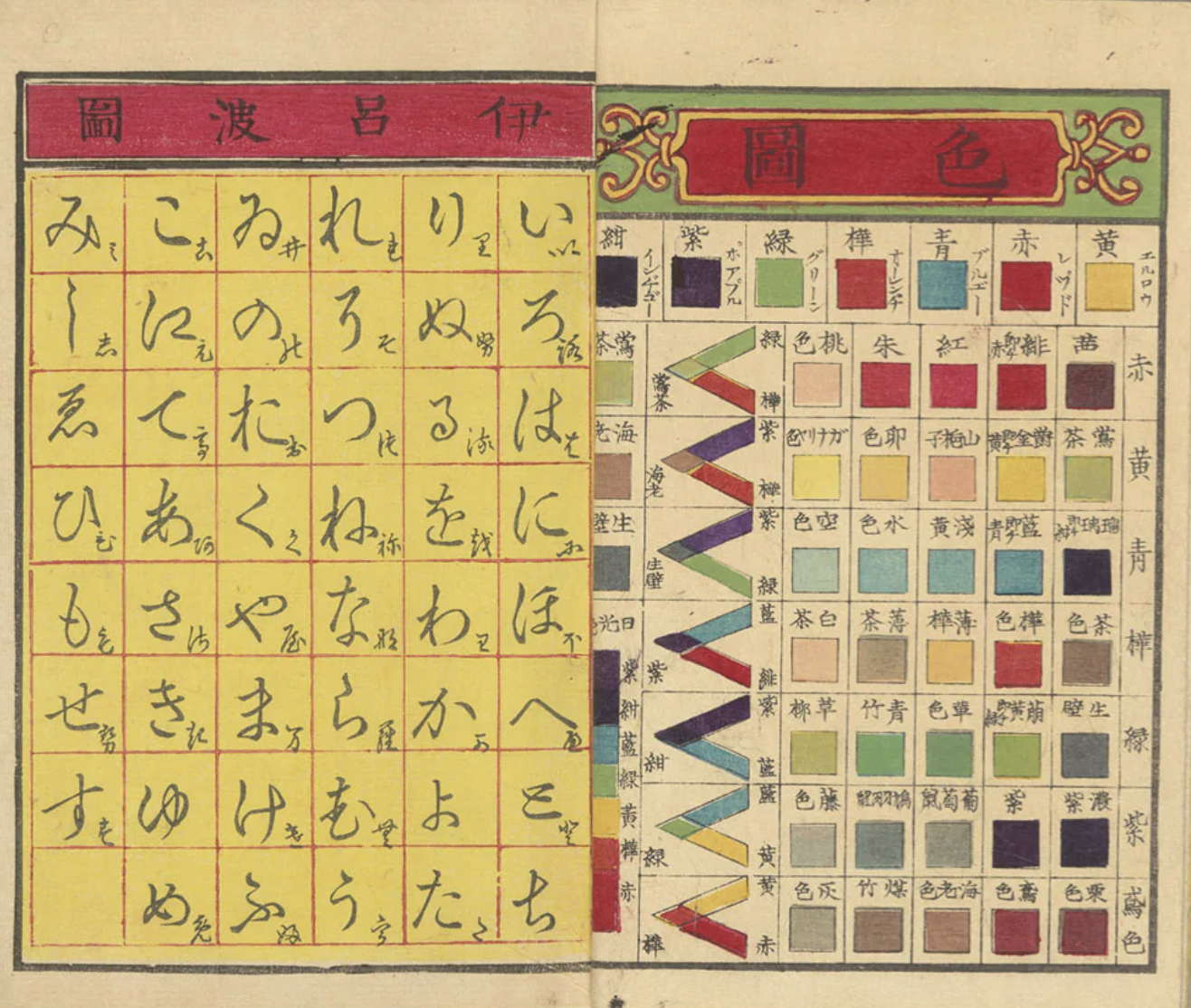

An Archive of Vividly Illustrated Japanese Schoolbooks, from the 1800s to World War II

If you want to appreciate Japanese books, it helps to be able to read Japanese books. It helps, but it’s not 100 percent necessary: even if you’ve never learned a single kanji character, you’ve probably marveled at one time or another at the aesthetics of Japan’s print culture. Maybe you’ve even done so here at Open Culture, where we’ve previously featured archives of Japanese books going back to the seventeenth century, a collection of Japanese wave and ripple designs from 1980, a Japanese edition of Aesop’s Fables from 1925, and even a fantastical history of America from 1861 — all of which display a heightened design sensibility not as easily found in other lands.

The same even holds true for Japanese schoolbooks and other educational materials, a digital archive of which you can explore on the web site of Japan’s National Institute for Educational Policy Research. “Ranging from brush painting guides to elementary readers to the geography of Koshi Province — now the Hokuriku region — hundreds of digital scans reveal what students were learning in school more than 100 years ago,” writes Colossal’s Kate Mothes.

(adsbygoogle = window.adsbygoogle || []).push({}); . -->Certain publications, like the epistolary 冨士野往来 (“Mount Fuji Comings and Goings”) from 1674, date back much further. But only a couple of centuries later did Japanese books start integrating the colorful artwork that still looks so vivid to us today. You’ll find particularly rich examples of such books in the sections of the archive dedicated to educational pictures, wall charts, and sugoroku, a kind of traditional board game.

Originally produced, for the most part, in the mid-to-late nineteenth century (though with some items as recent as the time of World War II), these provide a look at the worldview that Japan presented to its young students during a period when, not long emerged from more than 200 years of deliberate isolation, the country was taking in foreign influence — and especially Western influence — at a breakneck pace.

But despite a variety of proposed dramatic language reforms (which would later include the wholesale adoption of English), Japan would continue almost exclusively to speak and read Japanese. If you’re interested in learning it yourself, the reading materials in this archive will surely work as well for you as they did for the students of the eighteen-nineties. And even if you’re not, they’re still timeless object lessons in educational illustration and design. Enter the collection here.

via Colossal/Present & Correct

Related content:

Download Classic Japanese Wave and Ripple Designs: A Go-to Guide for Japanese Artists from 1903

Based in Seoul, Colin Marshall writes and broadcasts on cities, language, and culture. His projects include the Substack newsletter Books on Cities, the book The Stateless City: a Walk through 21st-Century Los Angeles and the video series The City in Cinema. Follow him on Twitter at @colinmarshall or on Facebook.

Free: Download the The Anarchist’s Tool Chest, The Anarchist’s Design Book, The Anarchist’s Workbench & Other Woodworking Texts

For Christopher Schwarz, American anarchism isn’t “about bombs and leather jackets; it’s about being an independent designer.” It’s about working outside “massive and dehumanizing institutions” (like corporations) and designing beautiful objects that last. He writes: “As a designer of books, tools and furniture, I have zero desire to make things that are intended from the get-go to fall apart.” Based in Covington, Kentucky, Schwarz runs a small woodworking business where he handcrafts beautiful tables, chairs and other pieces of furniture. He also runs Lost Art Press, which publishes books like The Anarchist’s Tool Chest, The Anarchist’s Design Book, The Anarchist’s Workbench, and other titles.

His “Anarchist” series of books “represent a 10-year effort to make woodworking more accessible, affordable and ethical – and less commercial.” Typically the print editions run $30-$54. But, to the delight of many fellow woodworkers, Schwarz has made several editions available as free digital downloads. This includes (as of this week) The Anarchist’s Tool Chest, which “shows you how you can build furniture with only a small kit of high-quality tools. The first half of the book explains in detail how to choose the right tools… The second half of the book shows you how to build a traditional tool chest to hold these tools.” To find a complete list of books available as free downloads, see the list below.

- The Anarchist’s Tool Chest

- The Anarchist’s Design Book

- The Anarchist’s Workbench

- The Art of Joinery

- Roman Workbenches

- The Stick Chair Book

How the Berlin Wall Worked: The Engineering & Structural Design of the Wall That Formidably Divided East & West

More than thirty years after the formal dissolution of the Union of Soviet Socialist Republics, few around the world have a clear understanding of how life actually worked there. That holds less for the larger political and economic questions than it does for the routine mechanics of day-to-day existence. These had a way of being even more complex in the regions where the USSR came up against the rest of the world. Take the German capital of Berlin, which, as everyone knows, was formerly divided into East and West along with the country itself — but which, as not everyone knows, but as clarified in a nineteen-eighties informational video previously featured here on Open Culture, was entirely surrounded by East Germany.

You can learn much else about life on the edges of the Federal Republic of Germany and the German Democratic Republic from the new neo video above, “How the Berlin Wall Worked.” The first thing to clarify is that, even after the division of Germany, the Berlin Wall wasn’t always there; for a time the narrator explains, with “socialism and capitalism, two different nations, and even two different currencies, were separated only by streets.”

(adsbygoogle = window.adsbygoogle || []).push({}); . -->Many “lived in one part of the city but worked in the other: East Berliners took jobs in the West in order to benefit from the stronger currency, while West Berliners got their haircuts in the East at prices that were much cheaper to them.” Kurfürstendamm’s shop windows displayed the purchasable glories of capitalism; just a few streets away, Stalinallee swelled with proudly socialist architecture.

But on August 13th, 1961, “Berlin woke up to a divided city.” The GDR immediately began on a wall between East and West “made out of concrete and topped off with barbed wire,” though it couldn’t command the resources to build its whole length quite so solidly right away. Over time, however, the wall was “consistently upgraded with more and more increasing security features.” By 1975, it had become the structure we remember, consisting of not just one but two concrete walls, and between them a barbed-wire signal fence, tank traps, mats of steel needles known as “Stalin’s grass,” and watchtowers manned by armed guards. “Virtually impossible to cross” in its day, the formidable Berlin Wall now exists primarily as a cultural phenomenon: a memory, a series of tourist sites, a sometimes-misused cultural reference. Living in South Korea, I can’t help but ask myself if the same will ever be said of the DMZ.

Related content:

See Berlin Before and After World War II in Startling Color Video

Google Revisits the Fall of the Iron Curtain in New Online Exhibition

Louis Armstrong Plays Historic Cold War Concerts in East Berlin & Budapest (1965)

Bruce Springsteen Plays East Berlin in 1988: I’m Not Here For Any Government. I’ve Come to Play Rock

Watch Samuel Beckett Walk the Streets of Berlin Like a Boss, 1969

Based in Seoul, Colin Marshall writes and broadcasts on cities, language, and culture. His projects include the Substack newsletter Books on Cities, the book The Stateless City: a Walk through 21st-Century Los Angeles and the video series The City in Cinema. Follow him on Twitter at @colinmarshall or on Facebook.

Google & MIT Offer a Free Course on Generative AI for Teachers and Educators

FYI. Google and MIT RAISE have partnered to create a free course for teachers and educators, one designed to show teachers how they can use generative AI tools to save “time on everyday tasks, personaliz[e] instruction to meet student needs, and enhanc[e] lessons and activities in creative ways.” According to the course description, in this two-hour self-paced course, teachers can learn how to use generative AI tools to:

- Create engaging lesson plans and materials. For example with generative AI, they can input their specific lesson plan and tailor it to student interests like explaining science using sports analogies.

- Tailor instruction for different abilities. Imagine a teacher who has 25 or 30 kids in their classroom. With generative AI, that teacher can easily modify the same lesson for different reading levels in their class.

- Save time on everyday tasks like drafting emails and other correspondence. For instance, if a student is out sick teachers can create summaries of that day’s lessons to help make sure the student doesn’t fall behind.

For those teachers who complete the course, they will “earn a certificate that they can present to their district for professional development (PD) credit, depending on district and state requirements.” Sign up for the course here.

Related Content

Generative AI for Everyone: A Free Course from AI Pioneer Andrew Ng

Amazon Offers Free AI Courses, Aiming to Help 2 Million People Build AI Skills by 2025

Noam Chomsky on ChatGPT: It’s “Basically High-Tech Plagiarism” and “a Way of Avoiding Learning”

How the Year 2440 Was Imagined in a 1771 French Sci-Fi Novel

Many Americans might think of Rip Van Winkle as the first man to nod off and wake up in the distant future. But as often seems to have been the case in the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries, the French got there first. Almost 50 years before Washington Irving’s short story, Louis-Sébastien Mercier’s utopian novel L’An 2440, rêve s’il en fut jamais (1771) sent its sleeping protagonist six and a half centuries forward in time. Read today, as it is in the new Kings and Things video above, the book appears in roughly equal parts uncannily prophetic and hopelessly rooted in its time — setting the precedent, you could say, for much of the yet-to-be-invented genre of science fiction.

Published in English as Memoirs of the Year Two Thousand Five Hundred (of which both Thomas Jefferson and George Washington owned copies), Mercier’s novel envisions “a world where some technological progress has been made, but the industrial revolution never happened. It’s a world where an agrarian society has invented something resembling hologram technology, where Pennsylvania is ruled by an Aztec emperor, and drinking coffee is a criminal offense.” Its setting, Paris, “has been completely reorganized. The chaotic medieval fabric has made way for grand and beautiful streets built in straight lines, similar to what actually happened in Haussmann’s renovation a bit under a century after the book was published.”

Mercier couldn’t have known about that ambitious work of urban renewal avant la lettre any more than he could have known about the revolution that was to come in just eighteen years. Yet he wrote with certainty that “the Bastille has been torn down, although not by a revolution, but by a king.” Mercier’s twenty-fifth-century France remains a monarchy, but it has become a benevolent, enlightened one whose citizens rejoice at the chance to pay tax beyond the amount they owe. More realistically, if less ambitiously, the book’s unstuck-in-time hero also marvels at the fact that traffic traveling in one direction uses one side of the street, and traffic traveling in the other direction uses the other, having come from a time when roads were more of a free-for-all.

L’An 2440, rêve s’il en fut jamais offers the rare example of a far-future utopia without high technology. “If anything, France is more agrarian than in the past,” with no interest even in developing the ability to grow cherries in the wintertime. Many of the inventions that would have struck Mercier’s contemporary readers as fantastical, such as an elaborate device for replicating the human voice, seem mundane today. Nevertheless, it all reflects the spirit of progress that was sweeping Europe in the late eighteenth century. Mercier was reformer enough to have his country abandon slavery and colonialism, but French enough to feel certain that la mission civilisatrice would continue apace, to the point of imagining that the French language would be widely spoken in China. These days, a sci-fi novelist would surely put it the other way around.

Related content:

The Oldest Voices That We Can Still Hear: Hear Audio Recordings of Ghostly Voices from the 1800s

In 1896, a French Cartoonist Predicted Our Socially-Distanced Zoom Holiday Gatherings

How French Artists in 1899 Envisioned What Life Would Look Like in the Year 2000

1902 French Trading Cards Imagine “Women of the Future”

A 1947 French Film Accurately Predicted Our 21st-Century Addiction to Smartphones

Based in Seoul, Colin Marshall writes and broadcasts on cities, language, and culture. His projects include the Substack newsletter Books on Cities, the book The Stateless City: a Walk through 21st-Century Los Angeles and the video series The City in Cinema. Follow him on Twitter at @colinmarshall or on Facebook.

Why the Short-Lived Calvin and Hobbes Is Still One of the Most Beloved & Influential Comic Strips

If you know more than a few millennials, you probably know someone who reveres Calvin and Hobbes as a sacred work of art. That comic strip’s cultural impact is even more remarkable considering that it ran in newspapers for only a decade, from 1985 to 1995: barely an existence at all, by the standards of the American funny pages, where the likes of Garfield has been lazily cracking wise for 45 years now. Yet these two examples of the comic-strip form could hardly be more different from each other in not just their duration, but also how they manifest in the world. While Garfield has long been a marketing juggernaut, Calvin and Hobbes creator Bill Watterson has famously turned down all licensing inquiries.

That choice set him apart from the other successful cartoonists of his time, not least Charles Schulz, whose work on Peanuts had inspired him to start drawing comics in the first place. Calvin and Hobbes may not have its own toys and lunchboxes, but it does reflect a Schulzian degree of thoughtfulness and personal dedication to the work. Like Schulz, Watterson eschewed delegation, creating the strip entirely by himself from beginning to end. Not only did he execute every brushstroke (not a metaphor, since he actually used a brush for more precise line control), every theme discussed and experienced by the titular six-year-old boy and his tiger best friend was rooted in his own thoughts.

“One of the beauties of a comic strip is that people’s expectations are nil,” Watterson said in an interview in the twenty-tens. “If you draw anything more subtle than a pie in the face, you’re considered a philosopher.” However modest the medium, he spent the whole run of Calvin and Hobbes trying to elevate it, verbally but even more so visually. Or perhaps the word is re-elevate, given how his increasingly ambitious Sunday-strip layouts evoked early-twentieth-century newspaper fixtures like Little Nemo and Krazy Kat, which sprawled lavishly across entire pages. Even if there could be no returning to the bygone golden age of the comic strip, he could at least draw inspiration from its glories.

Ironically, from the perspective of the twenty-twenties, Watterson’s work looks like an artifact of a bygone golden age itself. In the eighties and nineties, when even small-town newspapers could still command a robust readership, the comics section had a certain cultural weight; Watterson has spoken of the cartoonist’s practically unmatched ability to influence the thoughts of readers day on a daily basis. In my case, the influence ran especially deep, since I became a Calvin and Hobbes-loving millennial avant la lettre while first learning to read through the Sunday funnies. It took no time at all to master Garfield, but when I started getting Calvin and Hobbes, I knew I was making progress; even when I didn’t understand the words, I could still marvel at the sheer exuberance and detail of the art.

Calvin and Hobbes also attracted enthusiasts of other generations, not least among other cartoonists. Joel Allen Schroeder’s documentary Dear Mr. Watterson features more than a few of them expressing their admiration for how he raised the bar, as well as for how his work continues to enrapture young readers. Its timelessness owes in part to its lack of topical references (in contrast to, say, Doonesbury, which I remember always being the most formidable challenge in my days of incomplete literacy), but also to its understanding of childhood itself. Like Stephen King, a creator with whom he otherwise has little in common, Watterson remembers the exotic, often bizarre textures reality can take on for the very young.

He also remembers that childhood is not, as J. M. Coetzee once put it, “a time of innocent joy, to be spent in the meadows amid buttercups and bunny-rabbits or at the hearthside absorbed in a storybook,” but in large part “a time of gritting the teeth and enduring.” Being six years old has its pleasures, to be sure, but it also comes with strong doses of tedium, powerlessness, and futility, which we tend not to acknowledge as adults. Calvin and Hobbes showed me, as it’s shown so many young readers, that there’s a way out: not through studiousness, not through politeness, and certainly not through following the rules, but through the power of the imagination to re-enchant daily life. If it gets you sent to your room once in a while, that’s a small price to pay.

Related content:

How to Make Comics: A Four-Part Series from the Museum of Modern Art

17 Minutes of Charles Schulz Drawing Peanuts

Based in Seoul, Colin Marshall writes and broadcasts on cities, language, and culture. His projects include the Substack newsletter Books on Cities, the book The Stateless City: a Walk through 21st-Century Los Angeles and the video series The City in Cinema. Follow him on Twitter at @colinmarshall or on Facebook.

Beavis and Butt-Head on SNL

If you need six minutes of comic relief, this might do the trick. For those who don’t get the underlying reference, watch here. Enjoy! :)

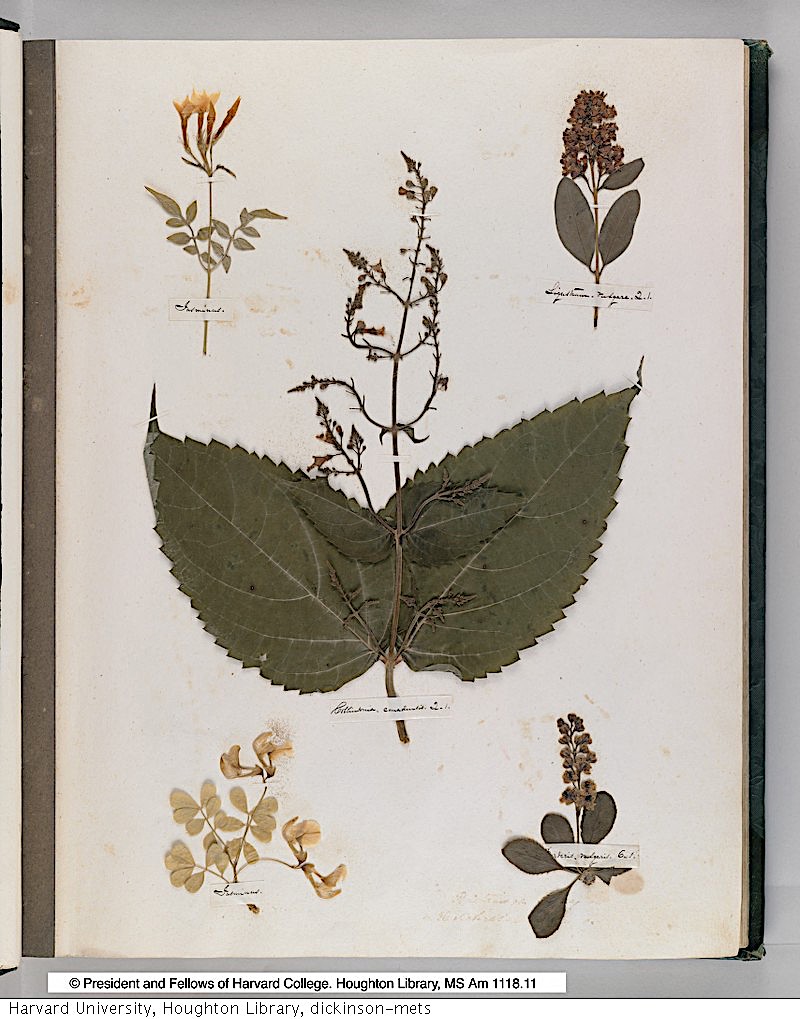

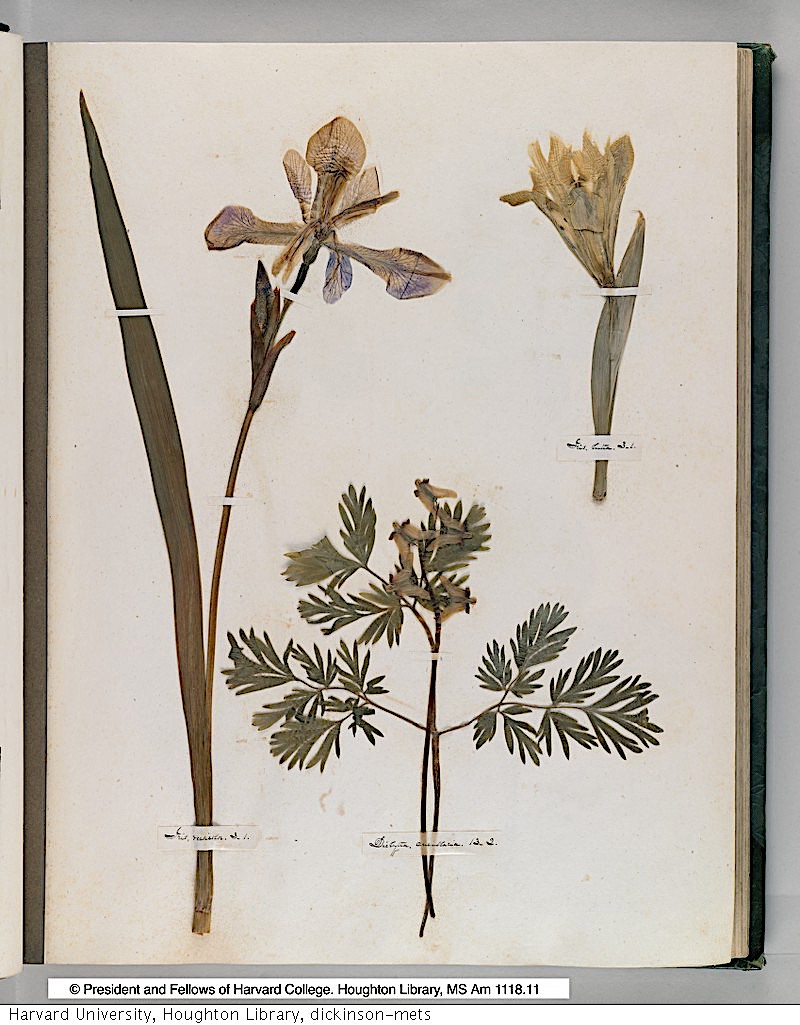

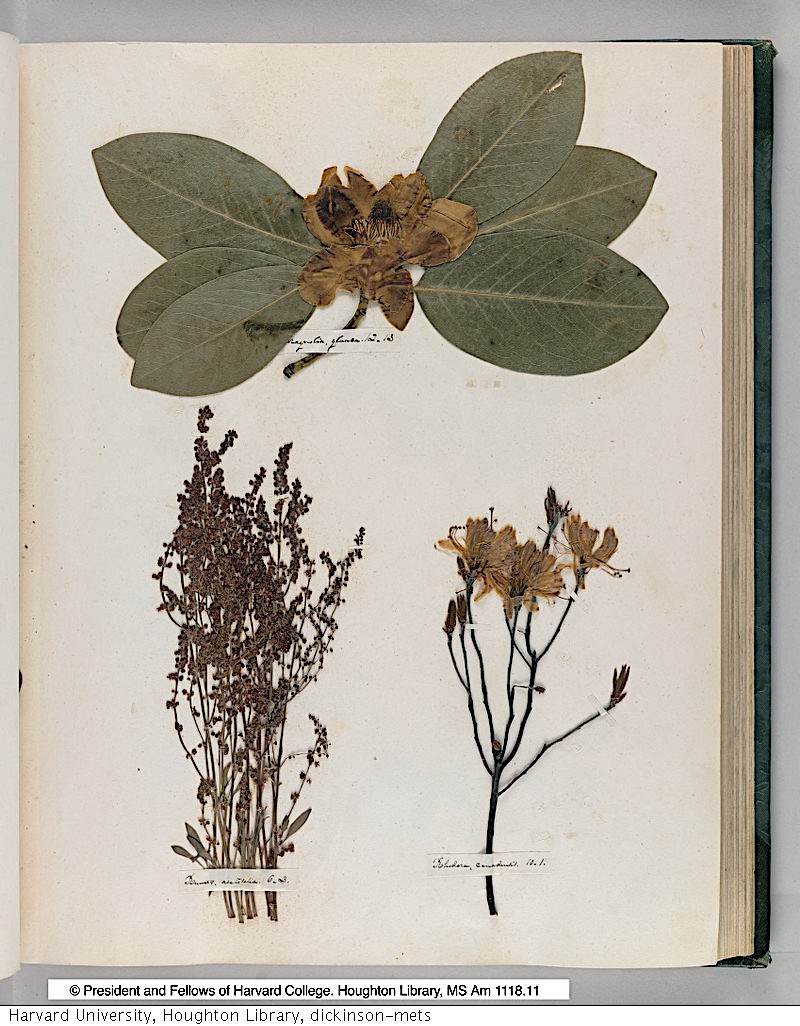

Emily Dickinson’s Herbarium: A Beautiful Digital Edition of the Poet’s Pressed Plants & Flowers Is Now Online

So many writers have been gardeners and have written about gardens that it might be easier to make a list of those who didn’t. But even in this crowded company, Emily Dickinson stands out. She not only attended the fragile beauty of flowers with an artist’s eye—before she’d written any of her famous verse—but she did so with the keen eye of a botanist, a field of work then open to anyone with the leisure, curiosity, and creativity to undertake it.

“In an era when the scientific establishment barred and bolted its gates to women,” Brain Pickings’ Maria Popova writes, “botany allowed Victorian women to enter science through the permissible backdoor of art.”

(adsbygoogle = window.adsbygoogle || []).push({}); . -->In Dickinson’s case, this involved the pressing of plants and flowers in an herbarium, preserving their beauty, and in some measure, their color for over 150 years. The Harvard Gazette describes this very fragile book, made available in 2006 in a full-color digital facsimile on the Harvard Library site:

Assembled in a patterned green album bought from the Springfield stationer G. & C. Merriam, the herbarium contains 424 specimens arranged on 66 leaves and delicately attached with small strips of paper. The specimens are either native plants, plants naturalized to Western Massachusetts, where Dickinson lived, or houseplants. Every page is accompanied by a transcription of Dickinson’s neat handwritten labels, which identifies each plant by its scientific name.

The book is thought to have been finished by the time she was 14 years old. Long part of Harvard’s Houghton Library collection, it has also long been treated as too fragile for anyone to view. The only access has come in the form of grainy, black and white photographs. For the past few years, however, scholars and lovers of Dickinson’s work have been able to see the herbarium in these stunning reproductions.

The pages are so formally composed they look like paintings from a distance. Though mostly unknown as a poet in her life, Dickinson was locally renowned in Amherst as a gardener and “expert plant identifier,” notes Sara C. Ditsworth. The herbarium may or may not offer a window of insight into Dickinson’s literary mind. Houghton Library curator Leslie A. Morris, who wrote the forward to the facsimile edition, seems skeptical. “I think that you could read a lot into the herbarium if you wanted to,” she says, “but you have no way of knowing.”

And yet we do. It may be impossible to separate Dickinson the gardener and botanist from Dickinson the poet and writer. As Ditsworth points out, “according to Judith Farr, author of The Gardens of Emily Dickinson, one-third of Dickinson’s poems and half of her letters mention flowers. She refers to plants almost 600 times,” including 350 references to flowers. Both her herbarium and her poetry can be situated within the 19th century “language of flowers,” a sentimental genre that Dickinson made her own, with her elliptical entwining of passion and secrecy.

The first two specimens in Dickinson’s herbarium are the jasmine and the privet: “You have jasmine for poetry and passion” in the language of flowers, Morris points out, “and privet,” a hedge plant, “for privacy.” There is no need to see this arrangement as a prediction of the future from the teenage botanist Dickinson. Did she plan from adolescence to become a recluse poet in later life? Perhaps not. But we can certainly “read into” the language of her herbarium some of the same great themes that recur over and over in her work, carried across by images of plants and flowers. See Dickinson’s complete herbarium at Harvard Library’s digital collections here, or purchase a (very expensive) facsimile edition of the book here.

Note: Note: An earlier version of this post appeared on our site in 2019.

Related Content:

How Emily Dickinson Writes A Poem: A Short Video Introduction

The Second Known Photo of Emily Dickinson Emerges

Josh Jones is a writer and musician based in Durham, NC. Follow him at @jdmagness

Who’s Behind These Scammy Text Messages We’ve All Been Getting?: The Search Engine Podcast Demystifies the Global Scam

You have received those odd text messages from a stranger. (“Hi, This is Anita. Have you received the Panamera parts yet?”) You know the messages are spam, but you don’t quite understand the angle of the scam. Above, the Search Engine podcast works with Bloomberg reporter Zeke Faux to break down the con operation. The story turns out to be more complicated than it first appears. It involves crypto, but also human trafficking and forced labor compounds in Cambodia and Myanmar. We’ll just leave it at that and suggest you listen to this unnerving podcast episode. You can hopefully stream it above or find it on your favorite podcast platform—e.g., Apple and Spotify.

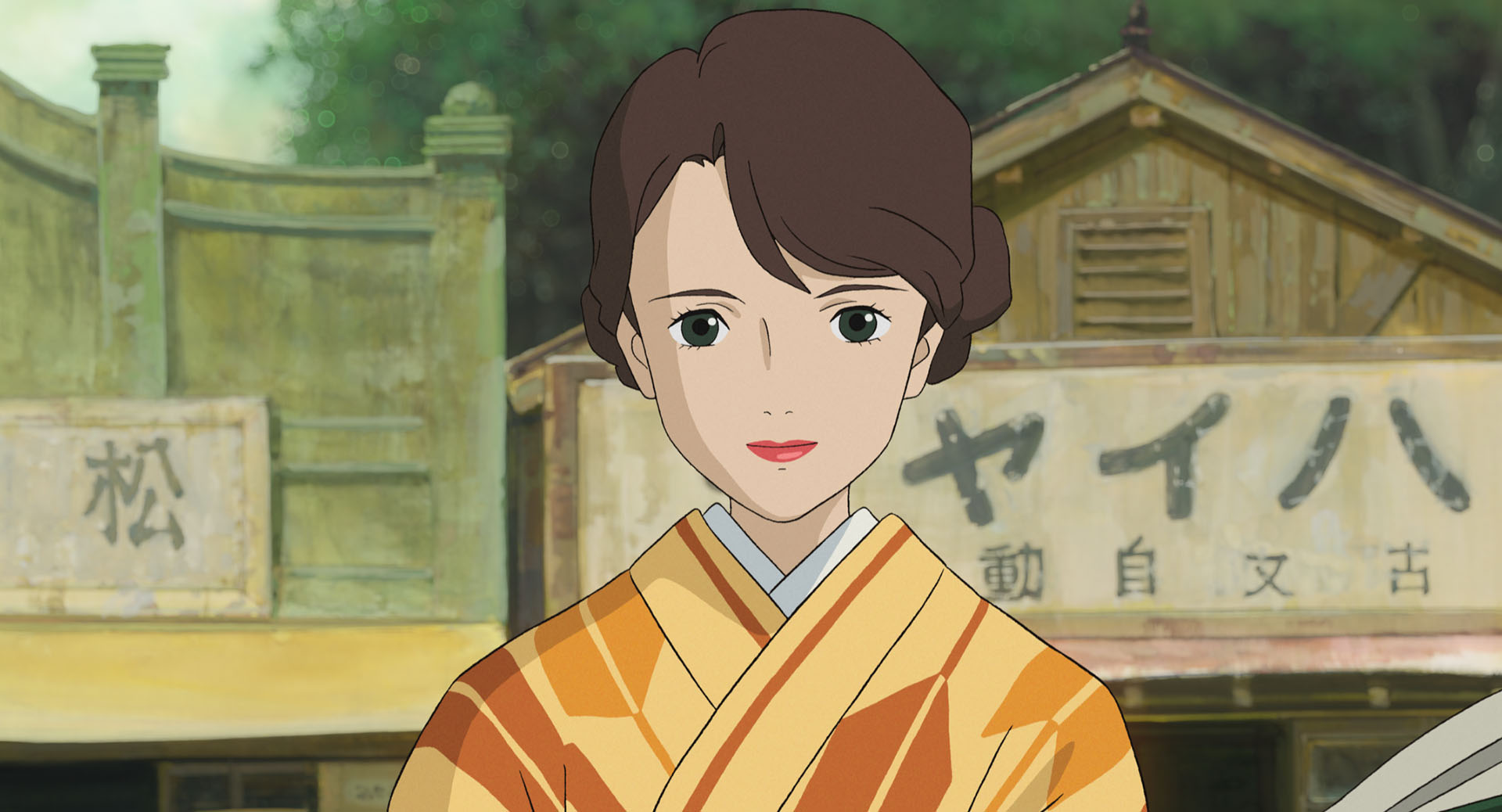

Studio Ghibli Lets You Download Free Images from Hayao Miyazaki’s “Final” Film, The Boy and the Heron

Studio Ghibli fans are still pondering the meaning of Hayao Miyazaki’s The Boy and the Heron, which came out last year. Though by some measure the studio’s most lavish feature yet — not least by the measure of it being the most expensive film yet produced in Japan — it’s also the one least amenable to simple interpretation. Even more so than in his previous work, Miyazaki seems to have intended to make a movie less to be explained than to be experienced. Just as the titular young protagonist descends into a bizarre but captivating underworld and returns, changed, to reality, so does the viewer.

If you’ve seen The Boy and the Heron, hearing its very title (which in Japan is 君たちはどう生きるか, or How Do You Live?) will bring back to mind a host of vivid images: the roving back of bulbous-featured grannies obsessed with non-perishable foodstuffs; the posturing of the middle-age Birdman, stuffed into his avian flight suit; the pyrotechnic feats of the young Lady Himi; and above all, perhaps, the floating cascades of Warawara, those adorably round spirits who — in painstaking Ghibli fashion — appear to have been animated individually, each with its own personality. Now, you can download stills from these and other scenes at Studio Ghibli’s official web site.

These come as an expansion to Ghibli’s existing collection, previously featured here on Open Culture, of free-to-download images from their library of titles. They’re offered, the site explains, “solely for personal use by individual fans to further enjoy Studio Ghibli films.” And indeed, they may have no effect stronger than making you want to watch The Boy and the Heron again, the more deeply to feel what Miyazaki intended with his “final” picture. Not that the latest of his retirements has stuck: last fall, Ghibli president Toshio Suzuki reported that the octogenarian Miyazaki was back in the office, planning his next film. If he has more realms yet to explore, animation-lovers around the world will surely follow him. Find the images from The Boy and the Heron here.

via My Modern Met

Related content:

Studio Ghibli Producer Toshio Suzuki Teaches You How to Draw Totoro in Two Minutes

Software Used by Hayao Miyazaki’s Animation Studio Becomes Open Source & Free to Download

Based in Seoul, Colin Marshall writes and broadcasts on cities, language, and culture. His projects include the Substack newsletter Books on Cities, the book The Stateless City: a Walk through 21st-Century Los Angeles and the video series The City in Cinema. Follow him on Twitter at @colinmarshall or on Facebook.

The Fictional Brand Archives: Explore a Growing Collection of Iconic But Fake Brands Found in Movies & TV

Los Pollos Hermanos, Madrigal Electromotive, Mesa Verde Bank and Trust, Davis & Main: Attorneys at Law—all of these brands come from the Breaking Bad/Better Call Saul universe. They also appear in the Fictional Brands Archive, a website dedicated to “fictional brands found in films, series and video games.” Taking the brands seriously as brands, the site draws on research from a new book written by Lorenzo Bernini entitled Fictional Brand Design. And, with its many entries, the site provides a “comprehensive view of each fictional brand, framing them in their own fictional context and documenting their use and execution in source work.”

Other notable brands include Acme (Looney Tunes), ATN News (Succession), Dunder Mifflin (The Office), Federal Motor Corporation (Fight Club), both Grand Budapest Hotel and Mendl’s (Grand Budapest Hotel), and Nakatomi Corporation (Die Hard). Enter the Fictional Brands Archive here.

Related Content

The Letterform Archive Launches a New Online Archive of Graphic Design, Featuring 9,000 Hi-Fi Images

Download 2,000 Magnificent Turn-of-the-Century Art Posters, Courtesy of the New York Public Library

40 Years of Saul Bass’ Groundbreaking Title Sequences in One Compilation

Ernest Hemingway’s Advice to Aspiring, Young Writers (1935)

Here in the twenty-twenties, a hopeful young novelist might choose to enroll in one of a host of post-graduate programs, and — with luck — there find a willing and able mentor. Back in the nineteen-thirties, things worked a bit differently. “In the spring of 1934, an aspiring writer named Arnold Samuelson hitchhiked from Minnesota to Florida to see if he could land a meeting with his favorite author,” says Nicole Bianchi, narrator of the InkWell Media video above. “The writer he had picked to be his mentor? Ernest Hemingway.”

What Hemingway offered Samuelson was something more than a literary mentorship. “This young man had one other obsession,” Hemingway writes in a 1935 Esquire piece. “He had always wanted to go to sea.” And so “we gave him a job as a night watchman on the boat which furnished him a place to sleep and work and gave him two or three hours’ work each day at cleaning up and a half of each day free to do his writing.” To Hemingway’s irritation, Samuelson proved not just a clumsy hand on the Pilar, but a fount of questions about how to craft literature — something Hemingway gives the impression of considering easier done than said.

(adsbygoogle = window.adsbygoogle || []).push({}); . -->Nevertheless, in the Esquire piece, Hemingway condenses this long back-and-forth with Samuelson into a dialogue containing lessons that “would have been worth fifty cents to him when he was twenty-one.” He first declares that “good writing is true writing,” and that such truth depends on the writer’s conscientiousness and knowledge of life. As for the value of imagination, “the more he learns from experience the more truly he can imagine.” But even the most world-weary novelist must “convey everything, every sensation, sight, feeling, place and emotion to the reader,” and that requires round after round of revision, so you might as well do the first draft in pencil.

As far as the writing itself, Hemingway recommends reading over at least your last two or three chapters at the start of each day, and repeats his well-known dictum always to leave a little water in the well at the end so that “your subconscious will work on it all the time.” But all will be for naught if you haven’t read enough great books so as to “write what hasn’t been written before or beat dead men at what they have done.” Don’t compete with living writers, whom Hemingway saw as propped up by “critics who always need a genius of the season, someone they understand completely and feel safe in praising, but when these fabricated geniuses are dead they will not exist.”

The video focuses on a series of mental exercises Hemingway explains to Samuelson. Recall an exciting experience, such as that of catching a fish, and “find what gave you the emotion, what the action was that gave you the excitement. Then write it down making it clear so the reader will see it too and have the same feeling you had.” Remember conflicts and try to understand all the points of view: “If I bawl you out try to figure out what I’m thinking about as well as how you feel about it. If Carlos curses Juan think what both their sides of it are. Don’t just think who is right.” When other people talk, “listen completely. Don’t be thinking what you’re going to say.”

Underlying this characteristically straightforward advice is the commandment to find ways out of your own head and into the perspective of the rest of humanity. The necessary habits of observation can be cultivated anywhere: at sea, yes, but also in the city, where you can “stand outside the theatre and see how people differ in the way they get out of taxis or motor cars.” In the event, Samuelson never did become a novelist, though he did write a memoir about his year under Hemingway’s tutelage. Whatever the experience taught Samuelson, it brought Hemingway to a resolution of his own: “If any more aspirant writers come on board the Pilar let them be females, let them be very beautiful and let them bring champagne.”

Related content:

7 Tips From Ernest Hemingway on How to Write Fiction

The (Urban) Legend of Ernest Hemingway’s Six-Word Story: “For sale, Baby shoes, Never worn”

18 (Free) Books Ernest Hemingway Wished He Could Read Again for the First Time

Ernest Hemingway Creates a Reading List for a Young Writer (1934)

Based in Seoul, Colin Marshall writes and broadcasts on cities, language, and culture. His projects include the Substack newsletter Books on Cities, the book The Stateless City: a Walk through 21st-Century Los Angeles and the video series The City in Cinema. Follow him on Twitter at @colinmarshall or on Facebook.

67 Logical Fallacies Explained in 11 Minutes

Fallacies—notes Purdue’s Writing Lab—“are common errors in reasoning that will undermine the logic of your argument. Fallacies can be either illegitimate arguments or irrelevant points, and are often identified because they lack evidence that supports their claim. Avoid these common fallacies in your own arguments and watch for them in the arguments of others.” Purdue’s website then highlights a number of the mental traps that students often fall into—for example, the slippery slope, begging the claim, circular arguments, the red herring, and more. But if you want a rapid-fire introduction to many more logical fallacies, look no further than the video above. In 11 minutes, you will come across ones you may not have known about before—from the No True Scotsman and the Texas Sharpshooter, to the Tu QuoQue and the Ignoratio Elenchi. But it also has some timeless ones we see every day. Indeed who among us hasn’t experienced the Sunk Cost Fallacy at work, or the Ad Hominem attack on TV?

Related Content

How Photos Were Transmitted by Wire in 1937: The Innovative Technology of a Century Ago

When did you last send someone a photo? That question may sound odd, owing to the sheer commonness of the act in question; in the twenty-twenties, we take photographs and share them worldwide without giving it a second thought. But in the nineteen-thirties, almost everyone who sent a photo did so through the mail, if they did it at all. Not that there weren’t more efficient means of transmission, at least to professionals in the cutting-edge newspaper industry: as dramatized in the short 1937 documentary above, the visual accompaniment to a sufficiently important scoop could also be sent in mere minutes through the miracle of wire.

“Traveling almost as fast as the telephone story, wired photos now go across the continent with the speed of light,” declares the narrator in breathless newsreel-announcer style. “It’s not a matter of sending the whole picture at once, but of separating the picture into fine lines, sending those lines over a wire, and assembling them at the other end.”

(adsbygoogle = window.adsbygoogle || []).push({}); . -->Illustrating this process is a clever mechanical prop involving two spindles on a hand crank, and a length of rope printed with the image of a car that unwinds from one spindle onto the other. To ensure the viewer’s complete understanding, animated diagrams also reveal the inner workings of the actual scanning, sending, and receiving apparatus.

This process may now seem impossibly cumbersome, but at the time it represented a leap forward for mass visual media. In the decades after the Second World War, the same basic principle — that of disassembling an image into lines at one point in order to reassemble it at another — would be employed in the homes and offices of ordinary Americans by devices such as the television set and fax machine. We know, as the viewers of 1937 didn’t, just how those analog technologies would change the character of life and work in the twentieth century. As for what their digital descendants will do to the twenty-first century, as they continue to break down all existence into not lines but bits, we’ve only just begun to find out.

Related content:

The History of Photography in Five Animated Minutes: From Camera Obscura to Camera Phone

Watch a Local TV Station Switch From Black & White to Color for First Time (1967)

Creative Uses of the Fax Machine: From Iggy Pop’s Bile to Stephen Hawking’s Snark

From the Annals of Optimism: The Newspaper Industry in 1981 Imagines its Digital Future

Based in Seoul, Colin Marshall writes and broadcasts on cities, language, and culture. His projects include the Substack newsletter Books on Cities, the book The Stateless City: a Walk through 21st-Century Los Angeles and the video series The City in Cinema. Follow him on Twitter at @colinmarshall or on Facebook.

Aldous Huxley, Dying of Cancer, Left This World Tripping on LSD (1963)

Aldous Huxley put himself forever on the intellectual map when he wrote the dystopian sci-fi novel Brave New World in 1931. (Listen to Huxley narrating a dramatized version here.) The British-born writer was living in Italy at the time, a continental intellectual par excellence.

Then, six years later, Huxley turned all of this upside down. He headed West, to Hollywood, the newest of the New World, where he took a stab at writing screenplays (with not much luck) and started experimenting with mysticism and psychedelics — first mescaline in 1953, then LSD in 1955. This put Huxley at the forefront of the counterculture’s experimentation with psychedelic drugs, something he documented in his 1954 book, The Doors of Perception.

(adsbygoogle = window.adsbygoogle || []).push({}); . -->Huxley’s experimentation continued until his death in November 1963. When cancer brought him to his deathbed, he asked his wife to inject him with “LSD, 100 µg, intramuscular.” He died tripping later that day, just hours after Kennedy’s assassination. Three years later, LSD was officially banned in California.

By way of footnote, it’s worth mentioning that the American medical establishment is now giving hallucinogens a second look, conducting controlled studies of how psilocybin and other psychedelics can help treat patients dealing with cancer, obsessive-compulsive disorder, post-traumatic stress disorder, drug/alcohol addiction and end-of-life anxiety.

For a look at the history of LSD, we recommend the 2002 film Hofmann’s Potion by Canadian filmmaker Connie Littlefield. You can watch it here.

If you would like to sign up for Open Culture’s free email newsletter, please find it here. Or follow our posts on Threads, Facebook, BlueSky or Mastodon.

If you would like to support the mission of Open Culture, consider making a donation to our site. It’s hard to rely 100% on ads, and your contributions will help us continue providing the best free cultural and educational materials to learners everywhere. You can contribute through PayPal, Patreon, and Venmo (@openculture). Thanks!

Related Content:

Ken Kesey’s First LSD Trip Animated

Aldous Huxley Predicts in 1950 What the World Will Look Like in the Year 2000

How Was the Great Pyramid Built?; What Did the Ancient Egyptian Language Sound Like?; Were There Bars in Ancient Egypt?: An Egyptologist Answers These Questions & More from Internet Users

What did ancient Egyptians sound like? What did they eat and drink? What ancient Egyptian medicine and tools do we still use in modern times? Why did they practice mummification? Above, Laurel Bestock, a professor from Brown University, discusses everything you ever wanted to know about Ancient Egypt. Not a stranger to popular media productions—Bestock appears in a recent National Geographic production, Egypt’s Lost Wonders—the professor fields every question that comes her way, no matter how big or small. All along, she gives “outstanding and very down-to-earth explanations,” notes a fellow professor in the YouTube comments. For my money, the best part comes at the 10:40 mark when she deciphers and reads hieroglyphs. Enjoy.

If you would like to sign up for Open Culture’s free email newsletter, please find it here. Or follow our posts on Threads, Facebook, BlueSky or Mastodon.

If you would like to support the mission of Open Culture, consider making a donation to our site. It’s hard to rely 100% on ads, and your contributions will help us continue providing the best free cultural and educational materials to learners everywhere. You can contribute through PayPal, Patreon, and Venmo (@openculture). Thanks!

Related Content

How to Read Ancient Egyptian Hieroglyphs: A British Museum Curator Explains

![Reference manager - [Onderhoud aantekeningen]](http://labyrinth.rienkjonker.nl/sites/default/files/styles/medium/public/Reference%20manager%20v3%20-%20%5BOnderhoud%20aantekeningen%5D%2014-2-2010%20102617_0.jpg?itok=OJkkWhxY)

![Reference manager - [Onderhoud aantekeningen]](http://labyrinth.rienkjonker.nl/sites/default/files/styles/medium/public/Reference%20manager%20v3%20-%20%5BOnderhoud%20aantekeningen%5D%2014-2-2010%20102628.jpg?itok=CUvhRRr7)

![Reference manager - [Onderhoud bronnen] - Opnemen en onderhouden](http://labyrinth.rienkjonker.nl/sites/default/files/styles/medium/public/Reference%20manager%20v3%20-%20%5BOnderhoud%20bronnen%5D%2014-2-2010%20102418.jpg?itok=d7rnOhhK)

![Reference manager - [Onderhoud bronnen]](http://labyrinth.rienkjonker.nl/sites/default/files/styles/medium/public/Reference%20manager%20v3%20-%20%5BOnderhoud%20bronnen%5D%2014-2-2010%20102433.jpg?itok=CgS8R6cS)

![Reference manager - [Onderhoud bronnen]](http://labyrinth.rienkjonker.nl/sites/default/files/styles/medium/public/Reference%20manager%20v3%20-%20%5BOnderhoud%20bronnen%5D%2014-2-2010%20102445_0.jpg?itok=4oJ07yFZ)

![Reference manager - [Onderhoud bronnen]](http://labyrinth.rienkjonker.nl/sites/default/files/styles/medium/public/Reference%20manager%20v3%20-%20%5BOnderhoud%20bronnen%5D%2014-2-2010%20102500.jpg?itok=ExHJRjAO)

![Reference manager - [Onderhoud bronnen]](http://labyrinth.rienkjonker.nl/sites/default/files/styles/medium/public/Reference%20manager%20v3%20-%20%5BOnderhoud%20bronnen%5D%2014-2-2010%20102524.jpg?itok=IeHaYl_M)

![Reference manager - [Onderhoud bronnen]](http://labyrinth.rienkjonker.nl/sites/default/files/styles/medium/public/Reference%20manager%20v3%20-%20%5BOnderhoud%20bronnen%5D%2014-2-2010%20102534.jpg?itok=cdKP4u3I)

![Reference manager - [Onderhoud thema's en rubrieken]](http://labyrinth.rienkjonker.nl/sites/default/files/styles/medium/public/Reference%20manager%20v3%20-%20%5BOnderhoud%20themas%20en%20rubrieken%5D%2020-9-2009%20185626.jpg?itok=zM5uJ2Sf)

![Reference manager - [Raadplegen aantekeningen]](http://labyrinth.rienkjonker.nl/sites/default/files/styles/medium/public/Reference%20manager%20v3%20-%20%5BRaadplegen%20aantekeningen%5D%2020-9-2009%20185612.jpg?itok=RnX2qguF)

![Reference manager - [Relatie termen (thesaurus)]](http://labyrinth.rienkjonker.nl/sites/default/files/styles/medium/public/Reference%20manager%20v3%20-%20%5BRelatie%20termen%20%28thesaurus%29%5D%2014-2-2010%20102751.jpg?itok=SmxubGMD)

![Reference manager - [Thesaurus raadplegen]](http://labyrinth.rienkjonker.nl/sites/default/files/styles/medium/public/Reference%20manager%20v3%20-%20%5BThesaurus%20raadplegen%5D%2014-2-2010%20102732.jpg?itok=FWvNcckL)

![Reference manager - [Zoek thema en rubrieken]](http://labyrinth.rienkjonker.nl/sites/default/files/styles/medium/public/Reference%20manager%20v3%20-%20%5BZoek%20thema%20en%20rubrieken%5D%2020-9-2009%20185546.jpg?itok=6sUOZbvL)

![Reference manager - [Onderhoud rubrieken]](http://labyrinth.rienkjonker.nl/sites/default/files/styles/medium/public/Reference%20manager%20v3%2020-9-2009%20185634.jpg?itok=oZ8RFfVI)

![Reference manager - [Onderhoud aantekeningen]](http://labyrinth.rienkjonker.nl/sites/default/files/styles/medium/public/Reference%20manager%20v3%20-%20%5BOnderhoud%20aantekeningen%5D%2014-2-2010%20102603.jpg?itok=XMMJmuWz)