U bent hier

Open source en open standaarden

Democratie, transparantie en honing in Rome

Op 11 en 12 oktober vond in Rome de Europese bijeenkomst van het Open Government Partnership, OGP, plaats. OGP is een internationale organisatie die met 77 nationale en 106 regionale overheden samen met maatschappelijke organisaties streeft naar bestuur dat transparant is, verantwoording aflegt en voortdurend burgers betrekt. Open State Foundation is als maatschappelijke partij vanuit Nederland aangesloten; Serv Wiemers nam aan de bijeenkomst deel.

In Rome ging het onder andere over de crises die de wereld nu treffen (na de coronapandemie de klimaatcrisis en de oorlog tegen Oekraïne). In tijden van crises kan de neiging bestaan gesloten op te treden, maar door iedereen te betrekken is een land juist sterker. Overheden moeten in gewone tijden al open zijn, en dan is het natuurlijk dat ook in tijden van crisis te zijn.

Maar in de praktijk staan vertrouwen en democratie wereldwijd onder druk. Openheid moet tegenwicht bieden tegen toenemend autoritarisme. Met digitale innovaties kunnen overheden inclusiever en meer ‘accountable’ worden. Het Nederlandse initiatief om transparantie rondom algoritmes te creëren werd als positief genoemd.

Op allerlei gebieden van open overheid konden de deelnemers aan de Europese OGP-bijeenkomst van elkaar leren: de relatie overheid-maatschappelijk middenveld, transparante lobby, communicatie, open aanbestedingen, enz. Wat dat laatste betreft was de aanwezigheid van een delegatie uit Oekraïne indrukwekkend. Overheid en maatschappelijk middenveld slaan daar de handen ineen om de komende wederopbouw maximaal transparant te laten verlopen.

Zo zorgt openheid voor de hoognodige vernieuwing van de democratie. ”Democracy should be like honey: sweet and sticky,” aldus de Chief Executive Officer of OGP, Sanjay Pradhan.

Foto: Serv Wiemers (op de rug gezien) aan een tafel met vertegenwoordigers van overheden, NGO’s en media voor het uitwisselen van best practices hoe de overheid tot meer openheid te bewegen.

Foto: Serv Wiemers (op de rug gezien) aan een tafel met vertegenwoordigers van overheden, NGO’s en media voor het uitwisselen van best practices hoe de overheid tot meer openheid te bewegen.

Implications from C-401/19 for National Transpositions in the Light of Freedom of Expression

COMMUNIA and Gesellschaft für Freiheitsrechte co-hosted the Filtered Futures conference on 19 September 2022 to discuss fundamental rights constraints of upload filters after the CJEU ruling on Article 17 of the Directive on Copyright in the Digital Single Market (CDSMD). This blog post is based on the author’s contribution to the conference’s first session “Fragmentation or Harmonisation? The impact of the Judgment on National Implementations.” It is published under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International licence (CC BY 4.0).

Article 17 of Directive (EU) 2019/790 on copyright in the Digital Single Market (CDSMD) has been subject to much debate even before its enactment. The latest twist is the CJEU’s ruling in the Polish action for annulment of Article 17 CDSMD. Uncertainties about the precise and correct practical application of Article 17 CDSMD remain. The judgment, however, provides some clarity on how this norm must be transposed into national law to ensure compliance with fundamental rights, particularly with freedom of expression and information as enshrined in Article 17(2) of the Charter of Fundamental Rights of the European Union.

Compatibility of verbatim transpositions and why the German approach is ahead of the packArticle 17 CDSMD is open to various interpretations – as has become clear during the hearings before the CJEU. While Spain and France argued that an implementation of ex post safeguards is sufficient to protect user rights, the CJEU later confirmed the position taken by the Advocate General and Member States like Germany that Article 17 CDSMD’s ex post safeguards must necessarily be supplemented by ex ante safeguards. These should address the danger of overblocking, that is the undue blocking of lawful content by OCSSPs before its dissemination in order to comply with the obligations from Article 17(4) CDSMD.

The judgment emphasises the need for ex ante safeguards against rampant blocking under Article 17(4) CDSMD. This fact, together with the obligation for Member States, when transposing Article 17 CDSMD, to strike a fair balance between the various fundamental rights, have raised doubts about the compatibility of verbatim transpositions. Other commentators have rejected these, arguing that minimal verbatim transposition is necessary to avoid impairing the harmonisation effect of the Directive.

The CJEU did not concern itself with national transpositions, but rather solely Article 17 CDSMD in its original version, and found an interpretation in compatibility with the freedom of expression. The CJEU held that Article 17(4) CDSMD is accompanied by appropriate safeguards. The judgment requires Member States to ensure an interpretation of national provisions that contains these safeguards.

As the judgment itself already identifies an interpretation of the Article in line with fundamental rights, the same must surely also apply to identical wording (i.e., copy and paste transpositions) in national law. This has to be the case as Member States are bound to interpret their laws in line with the CJEU’s interpretation. National courts, when interpreting national law, must have regard to the case law of the CJEU. Therefore, a conforming interpretation of verbatim transpositions should be ensured. As a consequence, copy and paste transpositions must be considered compatible with the judgment and the fundamental right to freedom of expression.

This does not mean, however, that this kind of implementation is the best in the face of freedom of expression and information. Instead, a more elaborative implementation, which provides more details on the delineation of permitted and prohibited ex ante blocking, should be the preferable way forward.

A conceivably elaborative implementation is the German version of Article 17 CDSMD, as it was transposed in the act on the copyright liability of OCSSPs (UrhDaG). One aspect of particular interest is the concept of a “presumed legal use”. In summary, Germany established a national additional ex ante safeguard for content which either qualifies as minor usage or is marked by the user as legally permitted. Under certain requirements, this content is presumed to be lawful and therefore cannot be blocked by automated means implemented by the OCSSPs. If rightholders contest this content, they have to initiate the complaint procedure, which may result in the content being taken down.

While there is an ongoing discussion about the compatibility of the German mechanism with the EU template, it is true that it dares to do something that had been missing from the EU Directive: it defines circumstances under which ex ante blocking is not possible.

The need for a definition of “manifestly infringing”It has to be said that while this constitutes a step in the right direction, the current German provisions may not be the ultimate solution. Rightholders argue that even the unjustified usage of a film sequence as short as 15 seconds can significantly harm their economic interests, when only blocked after an ex post intervention. Nevertheless, the German transposition puts requirements in black and white for the design and use of automated content recognition (ACR) technology and automated blocking based on it.

In order to protect freedom of expression, it is important to be more specific about the requirements and circumstances under which automated ex ante blocking of content is permissible. One of the key points from the judgment in the Polish case is that for content to be blocked ex ante without freedom of expression being unjustifiably harmed, no independent assessment of its unlawfulness must be necessary. In other words, content needs to be “manifestly infringing”, which makes this term the central standard for determining whether the prevention of an upload was lawful or not.

Therefore, it should not be left to OCSSPs to determine when content is infringing enough to be regarded as manifestly infringing and can thus lawfully be blocked automatically. Rather, regulators should find ways to define requirements. This would not only provide clarity to users, rightholders and platforms, but deployed at the EU level it would also contribute to the harmonisation objective.

The implementation of the German legislator may serve as a starting point. However, it only defines circumstances under which automated blocking is not permissible, i.e., when manifestly infringing content is not present. Therefore, the law only gives a hint of a negative definition. A positive definition, which indicates when content can be blocked automatically, has yet to be found.

Implications of the judgment for the design of the complaint mechanismIn the context of national transpositions of Article 17 CDSMD, two remarks regarding current questions of implementation should be made.

The first concerns national provisions in respect of the complaint mechanism as set out in Article 17(9) CDSMD. From the judgment in the Polish case, we know that the complaint mechanism is considered as an additional (ex post) safeguard, which applies in “cases where, notwithstanding the [ex ante] safeguards […], the providers of those services nonetheless erroneously or unjustifiably block lawful content” (para 93).

The complaint mechanism is therefore intended to deal with cases where there is a dispute as to whether the content is manifestly infringing. In those cases, however, it is in the nature of things that the content in question stays offline for the duration of the complaint mechanism. This presupposes that the basic requirements for ex ante safeguards have been implemented and that the ex post complaint mechanism only applies in exceptional cases. It is only under these conditions that provisions like the Italian one under which all contested content shall remain disabled for the duration of the complaint procedure can be considered compatible with the judgment.

The Commission’s category of “earmarked content” needs revisionThe second aspect relates to earmarked content as mentioned in the Commission’s Guidance on Article 17. The Guidance defines earmarked content as content flagged by rightholders that is particularly valuable and could cause them significant harm if it remains available without authorization (examples include pre-released music or films). According to the Guidance, earmarked content should be specifically taken into account when assessing whether OCSSPs have made their best efforts to ensure the unavailability of content.

What is highly problematic about this provision, however, is that OCSSPs would be forced to exercise particular care and diligence in this case, which would ultimately result in a higher blocking rate and ignore the requirements of the judgment in the Polish annulment action. As a solution, the Commission presents rapid ex ante human review in the Guidance, which takes place for such earmarked content before the content gets online, when detected by the filters.

This, however, does not comply with Article 17(8) CDSMD and what follows from the Glawischnig-Piesczek and recent Poland cases. According to these cases, a provider can only be required to remove content where a detailed legal examination is not necessary. And, although framed as “rapid ex ante review”, this is nothing other than a detailed legal examination.

Therefore, the Commission needs to revise its Guidance on this point and Member States should choose an implementation of earmarked content which respects the case law. A possible solution could be to use an earmark mechanism not ex ante but ex post. Content which is marked by rightholders as of significant economic value and matches content uploaded by users could be processed through an accelerated complaint procedure. This would be similar to what Article 19 of the Digital Services Act (DSA) establishes.

The DSA needs to fix Article 17 CDSMDThe DSA raises hopes for more harmonisation of details related to the interpretation of Article 17 CDSMD. Due to a largely overlapping scope of application for OCSSPs in the area of copyright, it can be assumed that the DSA provisions apply on the basis of a lex generalis relationship to Article 17 CDSMD. Provisions such as Article 17 DSA, that sets out detailed rules for a complaint mechanism, or Article 19 DSA, with its trusted flagger regime, could influence the way Article 17 CDSMD works in practice.

Due to its nature as a regulation, the DSA should lead to greater harmonisation. In order to achieve this, it would in addition be necessary to use the aforementioned revision of the Guidance to develop a positive definition of manifestly infringing content which can be used as a basis for designing the algorithms of OCSSPs.

The post Implications from C-401/19 for National Transpositions in the Light of Freedom of Expression appeared first on COMMUNIA Association.

The Impact of the German Implementation of Art. 17 CDSM Directive on Selected Online Platforms

Based on the joint paper with Alexander Peukert, “Coming into Force, not Coming into Effect? The Impact of the German Implementation of Art. 17 CDSM Directive on Selected Online Platforms.”

COMMUNIA and Gesellschaft für Freiheitsrechte co-hosted the Filtered Futures conference on 19 September 2022 to discuss fundamental rights constraints of upload filters after the CJEU ruling on Article 17 of the Directive on Copyright in the Digital Single Market (CDSMD). This blog post is based on the author’s contribution to the conference’s first session “Fragmentation or Harmonisation? The impact of the Judgement on National Implementations.” It is published under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International licence (CC BY 4.0).

On 26 April 2022, the CJEU dismissed the annulment action initiated by the Republic of Poland against Art. 17 CDSM Directive 2019/790 on copyright and related rights in the Digital Single Market (CDSMD): According to the Grand Chamber of the CJEU, the provision imposes a de facto obligation on service providers to use automatic content recognition tools in order to prevent copyright infringements by users of the platform. While this obligation leads to a limitation of the freedom of expression of users, appropriate and sufficient safeguards accompany the obligation, ensuring respect for the right to freedom of expression and information of users and a fair balance between that right and the right to intellectual property. However, guidelines of the CJEU as to how such safeguards have to be implemented in detail remain vague (C-401/19).

User safeguards in the German implementation

The Member States of the European Union follow different approaches when it comes to the implementation of Art. 17 CDSMD. The result is a legal fragmentation of platform regulations and uncertainty for service providers, rightholders and users alike as to the prerequisites under which OCSSPs have to operate. When the German Act on the Copyright Liability of Online Content Sharing Service Providers (OCSSP Act) entered into force imposing several detailed obligations on the service providers, many considered this new law as a model for the remaining implementations of other Member States. With its unique system, in which ex ante duties to block unlawful content are inseparably intertwined with ex ante duties to avoid the unavailability of lawful user content, the German OCSSP Act contains provisions which could pass as sufficient safeguard mechanisms in the meaning of the decision of the CJEU. In response to the debate on EU level and in other Member States, the OCSSP Act introduces a new category of “uses presumably authorised by law” – i.e., any statutory limitation to copyright –, which, as a rule, must not be blocked ex ante.

“Uses presumably authorised by law”, as laid down in sec. 9 of the OCSSP Act, can either be minor uses, which do not exceed the thresholds of sec. 10 OCSSP Act, or – if that is not the case – uses which the user flagged as legally authorised as per sec. 11 OCSSP Act. Both minor uses and flagged UGC must contain less than half of one or several other works (with an exception for images) and must combine this third-party content with other content. If these requirements are met cumulatively, the service provider must communicate the respective UGC to the public up until the conclusion of a complaints procedure. Thus, the category of “uses presumably authorised by law” enables the user to upload the content without interference by an automated copyright moderation tool. Rightholders, on the other side, are equipped not only with the possibility to initiate an internal complaints procedure but also with a “red button” which leads to the immediate blocking of content if it impairs the economic exploitation of premium content by the rightholder.

In sum, the German OCSSP Act provides a well-balanced legal framework. However, the quality of a statute is not only measured by its text and the concepts applied but also by the practical impact on the behaviour of its addressees. The question arises whether the OCSSP Act is able to deliver on its promises or if it turns out to be a toothless tiger in practice.

Effects of the German OCSSP Act

Against this background, Alexander Peukert and I have analysed whether the enactment of the German OCSSP Act in August 2021 had an immediate impact on platforms’ policies. The results of the study are compiled in a paper published in January 2022, which was the foundation for the presentation at the Filtered Futures conference on 19 September 2022 in Berlin. For the purpose of answering the question of what factual effect the OCSSP Act has actually had on the platform policies, the study examines the terms and conditions of several service providers both before and after the enactment of the OCSSP Act on 1 August 2021. We reviewed and analysed the German-language websites of eight services as to whether their terms and conditions and other publicly accessible copyright policies changed upon the entry into force of the German OCSSP Act. The data was collected at four points in time between July and November 2021. At all four points, we analysed the source-data as to whether the service provider implemented six selected mandatory duties, including the possibility for rightholders to submit reference files, the flagging option, the red button solution and a complaint system in accordance with the requirements of the OCSSP Act. With a total of 514 saved documents, including terms and conditions, general community and copyright guidelines, complaint forms, FAQs and other relevant copyright help pages, the paper allowed us to identify the practical effect of the German OCSSP Act over time on individual services, and across the eight services covered.

The results of the data collection are twofold. One the one hand, the changes which could be observed in the terms and conditions of the platforms over time are minor. On the other hand, there were differences between the service providers with regard to their compliance level with the statutory duties of the OCSSP Act already before its enactment (see table below).

Most changes we witnessed concerned the duty of the OCSSPs to guarantee a “notice and prevent” procedure. The flagging option, by contrast, was not clearly laid out in the terms and conditions of any service provider, at best vaguely indicated by YouTube and Facebook. The obligation of the service providers to inform their users about all statutory limitations under German copyright law in their terms and conditions was not fully met by the services, as they primarily referred to exceptions and limitations under “fair use” or EU law, but never to the exceptions and limitations under German copyright law.

Conclusions and outlook

In the conclusions of the paper, we raise the question of why larger platforms such as YouTube, Facebook and Instagram display a higher compliance with the OCSSP Act than comparatively small content sharing platforms. Furthermore, we note that it has become apparent that different Member State implementations and generally uncertain legal circumstances on the EU level impair the willingness of OCSSPs to take measures. It remains to be seen whether the decision of the CJEU will have any noticeable impact on the platform-side implementation. Lastly, the study brings to light the consequences of the lack of sanctions for failure to implement the user rights, in particular the regime regarding “uses presumably authorised by law”, i.e., minor or pre-flagged uses, in the German OCSSP Act.

In its essence, the study can serve as a starting point for further research. While the findings of the study reflect the changes of platform policies and primarily offer a text-based evaluation, they may provide incentives to investigate the upload process and other functionalities of the service providers further. More in-depth research on the legal and practical aspects of the new era of platform regulation is necessary to close the gap in legal doctrinal research on the implementation of Art. 17 CDSMD on platform level. The recently published decision of the CJEU and its emphasis on sufficient user safeguards adds fuel to this fire.

The post The Impact of the German Implementation of Art. 17 CDSM Directive on Selected Online Platforms appeared first on COMMUNIA Association.

The Uffizi vs. Jean Paul Gaultier: A Public Domain Perspective

With Teresa Nobre and Brigitte Vézina.

Two weeks ago, the Uffizi Gallery sent ripples through the open community by suing French fashion designer Jean Paul Gaultier for using Sandro Botticelli’s The Birth of Venus (1483) — which is on display in the Uffizi — in a clothing collection. Botticelli’s death in 1510 preceded the birth of copyright by centuries and his paintings are in the Public Domain worldwide. So on what grounds are the Uffizi taking action against Gaultier?

The answer lies not in copyright law but in the Italian cultural heritage code, Article 108 of Legislative Decree no. 42 of 2004 to be precise. This article of administrative law imposes a concession fee for the commercial reproduction of publicly owned works to be paid in advance to the institution delivering the work. Notably, the approach is also different from the concept of the Paying Public Domain or domaine public payant that exists in a number of African and Latin American countries and which taxes all uses of Public Domain works. Under the Italian cultural heritage code, fees need only to be paid for works that are held by Italian cultural heritage institutions and directly to that institution, not to the Italian state.

Cultural heritage laws should promote the public interestWe are aware of similar laws existing in Greece (Article 46 of Law no. 3028/2002 on the Protection of Antiques and Cultural Heritage in General), France (Article L621-42 of Code du Patrimoine) and Portugal (Administrative Order no. 10946/2014 on the Use of Images of Museums, Monuments and other Properties allocated to the Directorate-General for Cultural Heritage). Importantly, administrative law in general and this type of cultural heritage code in particular operate on a different logic than intellectual property law, as Simone Ariprandi explains in greater detail. Administrative law as an area of public law governs relations between legal persons and the state and not relations between private individuals. The intention is thus to promote the public interest and not to protect the private interests of authors.

The problem is that this law does quite the opposite of promoting the public interest by de facto curtailing the Public Domain. The Public Domain is an essential component not just of our copyright system, but essential to our social and economic welfare, as expressed in our Public Domain Manifesto:

[The Public Domain] is the basis of our self-understanding as expressed by our shared knowledge and culture. It is the raw material from which new knowledge is derived and new cultural works are created. The Public Domain acts as a protective mechanism that ensures that this raw material is available at its cost of reproduction — close to zero — and that all members of society can build upon it.

Imposing a fee for the use of certain Public Domain works restricts access to these public goods and thus stifles creativity. COMMUNIA is built on the conviction that the Public Domain must be upheld and guarded against attempts to enclose it from both public and private actors if we want to ensure the widest possible access to culture and knowledge and creativity to thrive.

Users should be trustedSo why do some EU countries exploit the physical ownership of works for which copyright has long expired? There are two main reasons, which from the perspective of national lawmakers might justify this measure. The first one is financial. The second one could be a paternalistic argument to retain some control over the artifacts held by national cultural heritage institutions and shield them against alleged misuse.

The financial argument does not stand up to a simple cost-benefit analysis. Fees collected through this mechanism do more harm than good, and any revenue generated is far outweighed by the heavy cost for members of society who are deprived of their fundamental right to access and enjoy culture, knowledge and information.

The notion that artists like Botticelli et al. and their work require protection from the general public is also easily dispelled. While we understand that masterpieces like the Birth of Venus are closely associated with the Uffizi and representative of Italian culture in general, this does not justify a financial barrier to the reuse of Public Domain works. There is also little evidence for the inappropriate use of Public Domain works, as stated in CC’s “What Are the Barriers to Open Culture?” report. Thus, we do not see a basis for retaining control by pricing out unwanted uses to ensure that no harm is caused to the reputation of the work, the author or the institution itself. We believe to the contrary that in an open society, the public must be trusted and enabled to make uses that are in line with fundamental freedoms, including freedom of expression.

It is unlikely that the Uffizi are worried that the commercial exploitation of the Birth of Venus per se would create a reputational risk, since this contradicts the institution’s own practice of exploiting its works of art for commercial gain. It is of course a question of personal taste whether one likes Gaultier’s printed multicolor tulle lounge pants or not. Yet a quick look at the Uffizi webshop reveals that the institution is by no means shy to market Botticelli’s masterpiece in similar ways. The visitor will find a shopping bag, a spectacle case (including a spectacle cloth), an oven glove and similar artifacts all incorporating Boticelli’s painting in some way or another. To be clear, the Uffizi should use works from their collection as they see fit to generate income. But to claim that museum professionals know better how to place the Birth on an oven glove is dubious at best.

Botticelli created the Birth of Venus during the 1480s — more than 500 years ago — and yet it remains so iconic not in spite of Jean Paul Gaultier, the Simpsons and other commercial creators referencing or incorporating the work but because of them. The transformative use of the Birth — even in a commercial context — doesn’t diminish the work, but keeps it relevant and ensures that it lives on as part of our cultural memory.

In sum, Italy’s cultural heritage code, although promoting important principles such as preservation and protection of heritage, poses a threat to the public domain, to the detriment of creators, reusers and society as a whole. While the best way forward is to remove this provision from the Italian cultural heritage code, there is in the meantime room for agency for cultural heritage institutions. Cultural heritage institutions can better fulfill their mission and still operate within the scope of the law by choosing not to request the payment of a fee by reusers of public domain heritage. The Uffizi should lead by example and withdraw its claim, and celebrate how cultural heritage is continuously being reinvented in new and unexpected ways through free creative expression.

The post The Uffizi vs. Jean Paul Gaultier: A Public Domain Perspective appeared first on COMMUNIA Association.

Implementation Imperatives for Article 17 CDSM Directive

COMMUNIA and Gesellschaft für Freiheitsrechte co-hosted the Filtered Futures conference on 19 September 2022 to discuss fundamental rights constraints of upload filters after the CJEU ruling on Article 17 of the Directive on Copyright in the Digital Single Market (CDSMD). This blog post is based on the author’s contribution to the conference’s first session “Fragmentation or Harmonisation? The impact of the Judgement on National Implementations.” It first appeared on Kluwer Copyright Blog and is here published under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International licence (CC BY 4.0).

The adoption of the CDSM Directive marked several turning points in EU copyright law. Chief amongst them is the departure from the established liability exemption regime for online content-sharing service providers (OCSSPs), a type of platform that (at the time) was singled out from the broader category of information society service providers regulated for the last 20 years by the E-Commerce Directive. To address a very particular problem – the value gap – Article 17 of the CDSM Directive changed (arguably, after the ruling in (YouTube/Cyando, C-682/18) the scope of existing exclusive rights, introduced new obligations for OCSSPs, and provided a suite of safeguards to ensure that the (fundamental) rights of users would be respected. The attempt to square this triangle resulted in a monstrosity of a provision. In wise anticipation of the difficulties Member States would face in implementing, and OCSSPs in operationalizing Article 17, the provision itself foresees a series of stakeholder dialogues, which were held in 2019 and 2020. Simultaneously, the drama was building up with a challenge launched by the Republic of Poland against important parts of Article 17. Following the conclusion of all these processes, and while (some) Member States are considering reasonable ways to transpose Article 17 into their national laws, it is time to take stock and to look ahead. The ruling in Poland v Parliament and Council (C-401/19) is a good starting point for such an exercise.

Shortly after the CDSM Directive was adopted, the Republic of Poland sought to annul those parts of Article 17 which it argued, and the Court later confirmed, effectively require OCSSPs to prevent (i.e. filter and block) user uploads. Preventing control of user uploads constitutes, the Court confirmed, a limitation of the right to freedom of expression as protected under Article 11 of the EU Charter of Fundamental Rights. In its argumentation Poland suggested that it might not be possible to cut up Article 17, a provision of ten lengthy paragraphs. Indeed, the intricate relations between specific obligations, new liability structures and substantive and procedural user safeguards cannot be seen in isolation, and therefore require a global assessment. And this is what the Court embarked upon. Whilst assessing the constitutionality of Article 17, the Luxembourg judges, in passing, provided some valuable insights into how a fundamental rights compliant transposition might look, but also left crucial questions unanswered.

The Court was very clear that any implementation of Article 17 – as a whole – must respect the various fundamental rights that are affected. However, the judges in Luxembourg did not go into detail on how Member States should transpose the provision. Of course, it is part of the nature of directives that Member States have a certain margin of discretion how the objectives pursued by a directive will be achieved. To complicate matters, the Court stated expressly that the limitation on the exercise of the right to freedom of expression contained in Article 17 was formulated in a ‘sufficiently open’ way so as to keep pace with technological developments. Together with the intricate structure of Article 17 itself, this openness tasks Member States with a difficult exercise: to arrive at a transposition of Article 17 (and of course also other provisions of the CDSM Directive) that achieves the objective pursued while respecting the various fundamental rights affected (see Geiger/Jütte). The various national implementation processes have already demonstrated that opinions differ as to what constitutes a fundamental rights compliant implementation, and proposals have been made at different points of the spectrum between rightsholder-friendly and user-friendly transpositions.

The Court’s ruling makes a few, very important statements in this respect and thereby sets the guardrails beyond which national transpositions should not venture. First and foremost, control of user uploads must be strictly targeted at unlawful uses without affecting lawful uses. Recognizing that the employment of online filters is necessary to ensure the effective protection of intellectual property rights, the ruling highlights the various safeguards that ensure that the limitation of the right to freedom of expression is a proportionate one. Implicit here is that the targeted filtering of user uploads is a limitation of this fundamental right that necessitates six distinct measures that must be put in place, and which, in concert, ensure respect for the rights of users on OCSSP platforms.

Targeted FilteringTo limit the negative effects of overblocking and overzealous enforcement, any intervention by OCSSPs must be aimed at bringing the infringement to an end and should not interfere with the rights of other users to access information on such services. This suggests that it must be clear that only unlawful, or infringing content is targeted. The Court elaborates that within the context of Article 17 only filters which can adequately distinguish between lawful and unlawful content, without requiring OCSSPs to make a separate legal assessment, are appropriate. This is problematic, since copyright infringements are context sensitive, in particular in relation to potentially applicable exceptions and limitations. Requiring rightholders to obtain court-ordered injunctions before content can be subject to preventive filtering and blocking seems unreasonable, considering the amount of information uploaded onto online platforms. On the one side, copyright infringements are different from instances of defamation or other offensive speech, that was the subject of the preliminary reference in Glawischnig-Piesczek (C-18/18). On the other, the requirement of targeted filtering seems to eliminate the proposal made by the Commission in its Guidance (see Reda/Keller) to allow rightholders to earmark commercially sensitive content, which could be subject to preventive filtering for a certain limited amount of time. Unfortunately, the Court does not elaborate further how OCSSPs can target their interventions. It merely states that rightholders must provide OCSSPs with the relevant and necessary information on unlawful content, which failure to remove would trigger liability under Article 17(4) (b) and (c). What this information must contain remains unclear. Arguably, rightholders must make it very clear that certain uploads are indeed infringing.

User SafeguardsIn terms of substantive safeguards, Article 17 takes a frugal approach. To avoid speech being unduly limited, it requires Member States to ensure that certain copyright exceptions must be available to users of OCSSPs. These exceptions are already contained in Article 5 of the Information Society Directive as optional measures, but Article 17(7) makes them mandatory (see Jütte/Priora). Arguably not much changes with the introduction of existing exceptions (now in mandatory form). Moreover, the danger of context-insensitive automated filtering still persists, even though users enjoy these substantive rights.

Therefore, Article 17 foresees procedural safeguards, which is where the balance in Article 17 is struck. With the Court having confirmed that preventive filtering is an extreme limitation of freedom of expression, the importance of the procedural safeguards cannot be overstated (see Geiger/Jütte). The ruling in its relevant parts can be described as anticlimactic. Instead of describing how effective user safeguards must be designed, the judgment merely underlines that these safeguards must be implemented in a way that ensures a fair balance between fundamental rights. How such balance can be achieved was demonstrated in summer 2022, when the Digital Services Act (which is still to be formally adopted) took shape. A horizontally applicable regulation that amends the E-Commerce Directive, the DSA puts flesh to the bones that the CDSM Directive so clumsily constructed into a normative skeleton.

The DSA provides far more detailed procedural safeguards compared to the CDSM Directive. It is also lex posterior to the latter, which in itself is, however, lex generalis to the former. Their relation, but arguably also their genesis, holds the key to outlining not necessarily the solution to the CDSM conundrum, but to the questions that national legislators must ask.

The DSA sets out how hosting services and online platforms must react to notifications of unlawful content and how they must handle complaints internally; the DSA also outlines a system for out-of-court dispute settlement, which requires certification by an external institution. Some of these elements are, in embryonic form as mere abstract obligations, already contained in the CDSM Directive’s Article 17. And by definition, OCSSPs are hosting providers and online platforms in the parlance of the DSA, which is why these rules should also apply to them. OCSSPs, however, incur special obligations and are exempted from the general liability of the E-Commerce Directive and (soon) the DSA, because they are more disruptive – of the use of works and other subject matter protected by copyright and of the rights of users, the latter as a result of obligations incurred because of the former.

That some of the rules introduced by the DSA must also apply to OCSSPs has been argued elsewhere (see Quintais/Schwemer). It has been suggested that the rules of the DSA should apply in areas in which the DSA leaves Member States a margin of discretion or where the CDSM Directive is silent. CDSM rules that derogate from those of the DSA, specifically the absence of a liability exemption for user uploaded content will certainly remain unaffected. But there are good arguments to be made why in areas of overlapping scope, the DSA should prevail, or systematically supplement the CDSM Directive. Instead, the DSA rules must form the floor of safeguards that Member States have to provide, and which should be elevated in relation to the activities of OCSSPs. The reason is a shifting of balance between the fundamental rights concerns, which relates to the last paragraph of the CJEU’s ruling in Poland v Parliament and Council. The obligation to proactively participate in the enforcement of copyright intensifies the intervention of OCSSPs, as opposed to the merely reactive intervention required under the rules of the DSA. The effects for rightholders are beneficial (although the rationale for Article 17 suggests that it addresses a technological injustice) in the sense that OCSSPs must intervene in a higher volume of cases; the negative effects are borne by users of platforms, their rights are limited as a result. Arguably, this must be balanced by a higher level of protection of users, in this case in the form of stronger and more robust procedural safeguards. A further elevation of substantive safeguards would in itself not be helpful, since their enjoyment relies effectively on procedural support.

As a result, Member States should, or even must, consider that the elaboration of user safeguards in the form of internal complaints mechanisms and out-of-court dispute settlement mechanisms must find concrete expression in their national transpositions. They should be more robust than those provided by the DSA. Ideally, this robustness will be written into national laws and not left to be defined by OCSSPs as executors of the indecisiveness of legislators. The difficulty lies, of course, in the uncertainty of technological process, the development of user behaviour and the rise and fall of platforms and their business models. Admittedly, some sort of flexibility is necessary, the Court has recognized this explicitly. But if the guardrails that guarantee compliance with fundamental rights are not, and possibly cannot be written into the law, they must be determined by another independent institution. One institution, understood more broadly, could be the stakeholder dialogues required pursuant to Article 17(10) CDSM Directive. The Court listed them as one of the applicable safeguards, and a continuous dialogue between OCSSPs, rightholders and users could serve to define these guardrails more concretely. Such a trilogue, however, must take as its point of departure the ruling in C-401/19 and learn from the misguided first round of stakeholder dialogues. Another institution that could progressively develop standards for user safeguards are formal independent institutions, such as the Digital Service Coordinators (DSCs) required under the DSA. There, they have the task, amongst others, of certifying out-of-court dispute settlement institutions and awarding the status of trusted flaggers. Their tasks could also include general supervision and auditing of OCSSPs with regard to their obligations arising not only under the DSA, but also under the CDSM Directive. In the context of the Directive, DSCs could also be tasked with developing and supervising a framework for rightholders as ‘trusted flaggers’ on online content-sharing platforms. The role of DSCs under the DSA and their potential role in relation to OCSSPs is still unclear. But the reluctance of the legislature to give substance to safeguards and to clarify the relation between the DSA and the CDSM Directive mandates that the delicate task of reconciling the reasonable interests of rightholders and the equally important and vulnerable interest of users be managed by independent arbiters. Leaving this mitigation to platform-based complaint mechanism or independent dispute settlement institutions is an easy solution. A constitutionally sound approach would try to solve these fundamental conflicts at an earlier stage instead of making private operators the guardians of freedom of expression and other fundamental rights. While the Court of Justice of the European Union has not stated this expressly, its final reference to the importance of implementing and applying Article 17 in light of, and with respect to fundamental rights can be understood as a warning not to take the delegation of sovereign tasks too lightly.

The post Implementation Imperatives for Article 17 CDSM Directive appeared first on COMMUNIA Association.

Reflecting the Conclusions of the CJEU? The Evolving Czech Implementation of Article 17

The Czech Republic is one of the last EU member States yet to implement the CDSM directive into national law. The Czech government had produced an initial draft of the implementation act in November 2020, which has since been moving through the legislative parliament. Last week, the Chamber of Deputies of the Czech Parliament adopted the implementation act in third reading and in doing so it has introduced a number of interesting improvements to the implementation of Article 17.

The initial Czech approach to implementing the provisions of Article 17 has been disappointing. The government’s draft bill was largely limited to restating the provisions of Article 17 without introducing any ex-ante safeguards against overblocking or any meaningful remedies for users whose uploads are blocked or removed by automated upload filters. The proposal also included a few positive elements, such as a targeted definition of OCSSPs and an amendment of the existing caricature and parody exception in the Czech copyright act to explicitly include pastiche.

In February of last year, we pointed out the shortcomings of the Article 17 implementation in a position paper that we published together with Open Content, Wikimedia CZ, Iuridicum Remedium and “Za bezpecny a svobodny internet“. In April of this year during the subsequent parliamentary proceedings, Pirate Party MP Klára Kocmanová tabled a set of amendments designed to introduce additional safeguards against overblocking into the text.

During last week’s third reading of the bill in the Chamber of Deputies, these amendments resulted in a much better national implementation of Article 17 that substantially alters the government’s original proposal and incorporates some practical rules for platforms to implement those obligations. This is especially interesting since the Czech Republic is one of the first countries to proceed with its implementation after the CJEU ruling in case C-401/19 has brought more clarity on the safeguards that need to be included in national implementations of Article 17.

The amendments adopted last week modify § 47 — which implements the licensing and filtering obligations from Article 17(4) — and introduce a new § 51(a).

Two new paragraphs were added to the proposed § 47 of the Copyright Act: A new paragraph (4), which implements the first sentence of Article 17(8) and proibits general monitoring of content uploaded by users of online platforms; and a new paragraph (3), which looks like an attempt to integrate the criteria developed by the Advocate General in his opinion in Case C-401/19 directly into the Czech Copyright Act. The latter limits the use of automated content recognition technologies that results in the blocking or removal of uploads to cases where the uploads are “identical or equivalent” to a work that rightholders have requested to be blocked. The Article further defines that (translation via deepl):

Identical content means identical content without additional elements or added value. Equivalent content means content which differs from the work identified by the author only by modifications which can be considered as insignificant without the need for additional information to be provided by the author and without a separate assessment of the lawfulness of the use of the work with modifications under this Act.

This language inserts one of the core findings of the CJEU ruling — that platforms can only be required to detect and block content on the basis of the information provided by rightholders and cannot be required to block content which, in order to be found unlawful, would require an independent assessment of the content by the platforms — into the Czech implementation. While it does so by referencing concepts developed by the AG, instead of the criteria from the final judgement, it is a welcome addition that will offer a better protection to users’ rights than the literal implementation proposed by the government.

The newly added § 51(a), on the other hand, introduces remedies for cases where platforms repeatedly block or remove lawful user uploads. As we have argued previously, one of the most problematic parts of Article 17 is that it includes strong incentives for platforms to remove user uploads (because they otherwise risk being held liable for copyright infringement) but does not clarify what kind of risks platforms face when their use of upload filters violates users’ freedom of expression.

The newly introduced § 51(a) of the Czech Copyright Act would address this issue by giving “legal persons authorised to represent the interests of competitors or users” the ability to request “a ban on the provision of the service” when platforms “repeatedly and unlawfully” block or remove works uploaded by their users (all translations via deepl).

A situation in which platforms risk getting shut down as a consequence of repeatedly curtailing their users’ freedom of speech at the behest of rightholders may be an interesting thought experiment —it would completely reverse the power relationships between platforms and their users —but ultimately shutting down platforms for such violations is a problematic and short-sighted remedy.

Is it really the intent of the Czech lawmaker to shut down a platform as a sanction for blocking or removing lawful uploads and under what conditions would such an extreme measure be imposed? The blocking of an entire platform is clearly counterproductive to the intent of promoting freedom of expression, as it would result in the inaccessibility of all content available on the platform. This makes the remedy introduced in § 51(a) disportionate, which is even more problematic since the article also implies that it can be invoked by competitors.

It is unclear how the drafters of the amendment envisage § 51(a) to work, but it seems clear that — as adopted by the Chamber of Deputies — it will do much more harm than good. While it provides a powerful incentive for platforms not to overblock, invoking this remedy would result in substantial collateral damage that negatively affects the freedom of expression of all other uses of the affected platform.

So what could a more reasonable — and less harmful— remedy look like? What if instead of threatening to shut down the offending platform, § 51(a) threatened to shut down the upload filters instead: If it would prohibit the provision of the automated content recognition (ACR) system for the purpose of blocking or removal of user uploads?

Such a remedy would be much more proportionate, as it addresses the root of the problem (the malfunctioning ACR system) instead of attacking the host (the platform). It would also not cause any collateral damage for other users of the offending platform. It would also be in line with the CJEU’s reasoning as it would prevent filtering systems that do not comply with the standards set by the court from being used.

Shutting down ACR systems that repeatedly overblock would still provide platforms with a powerful incentive to get their systems calibrated right. Given the overall volume of uploads that they have to deal with, platforms do have a very strong interest to be able to rely on automated filters for removing manifestly infringing uploads.

For all of these reasons it seems imperative that the Czech legislator takes another good look at the scope of the remedy introduced in § 51(a). Adding explicit remedies against overblocking is an important element of balanced national implementations, but in its current form the Czech approach risks throwing out the baby with the bathwater.

However, if the scope of the injunctive relief would be limited to banning the continued provisions of overzealous upload filters, the proposed Czech implementation of Article 17 could even become a template for other Member States seeking to bring their implementations in line with the requirements of the CJEU while otherwise staying relatively close to the text of the directive.

The post Reflecting the Conclusions of the CJEU? The Evolving Czech Implementation of Article 17 appeared first on COMMUNIA Association.

Stemlokalen in beeld GR 2022

Al jaren verzamelen bij elke verkiezing data over alle stemlokalen voor het platform WaarIsMijnStemlokaal.nl. Zo weet iedereen waar gestemd kan worden, hoe laat de deuren open gaan, of een stemlokaal rolstoelvriendelijk is en of er hulpmiddelen zoals een leesloep aanwezig zijn. Doordat alle stemlokaaldata verzameld wordt volgens de Stembureaus Open Data Standaard ontstaat er ook een eenduidige open dataset die door onder andere journalisten en onderzoekers hergebruikt kan worden binnen hun speurwerk. Met de stemlokaal data van de vorige verkiezingen zijn wij zelf ook aan de slag gegaan met het analyseren van deze dataset. Met als resultaat het rapport ‘Meting stemlokalen – Gemeenteraadsverkiezingen 2022‘.

Tijdens de afgelopen Gemeenteraadsverkiezingen in 2022 konden kiezers hun stem uitbrengen in 333 gemeenten in 8582 stemlokalen. Stemlokalen spelen een centrale rol bij verkiezingen en inzicht het aantal stemlokalen de kenmerken zijn fundamenteel binnen het evalueren van de verkiezingen kunnen op termijn de basis zijn voor beleidsontwikkeling ter verbetering van verkiezingen. Zijn stemlokalen toegankelijk voor mensen met een auditieve, visuele of fysieke beperking, wordt er gebruik gemaakt van het meerdaags stemmen, wat is de afstand naar een stemlokaal?

Uit deze nulmeting bleek onder andere dat de gemiddelde afstand tot een stemlokaal in Nederland 398 meter is. En dat naarmate de bevolkingsdichtheid toeneemt de afstand tot het stemlokaal korter wordt en naarmate de bevolkingsdichtheid afneemt er grotere afstanden tot bepaalde stemlokalen zijn. In totaal waren er tijdens de verkiezingen 16,3% van de stemlokalen op alle drie de dagen open. Gebouwen met het gebruiksdoel ‘bijeenkomst’ komen het meest voor: 46%. Gebouwen met een sport (15%) of onderwijsfunctie (12%) worden ook veel gebruikt.

Ben je benieuwd naar hoe we het onderzoek hebben uitgevoerd? Alle stappen die we hebben doorlopen zijn gedocumenteerd in dit Jupyter Notebook. Download het gehele rapport hier.

Global Civil Society Coalition Promotes Access to Knowledge

COMMUNIA is part of a group of civil society organizations from all around the globe that promotes access to, and use of, knowledge, the Access to Knowledge or A2K Coalition. COMMUNIA directors Justus Dreyling and Teresa Nobre have been co-initiators of the A2K Coalition.

Today, the A2K Coalition is launching its website with demands for education, research and cultural heritage.

Access to knowledge is not enjoyed equally across the world. Crises, including the COVID-19 pandemic and the climate emergency, highlight the barriers that the current copyright system poses for those who learn, teach, research, create, preserve or seek to enjoy the world’s cultural heritage.

The international copyright system has failed to keep pace with advancing technology and practices, including for digital and cross-border activities. Consequently, we have been unable to seize the possibilities that exist to promote access to, and use of, knowledge to fulfill human rights and achieve more equitable, inclusive and sustainable societies.

The members of the A2K Coalition represent educators, researchers, students, libraries, archives, museums, other knowledge users and creative communities around the globe. Our individual missions are varied but we all share a vision of a fair and balanced copyright system.

In addition to our mission statement and demands, the A2K Coalition website features evidence to substantiate our claims. Three maps track the state of copyright limitations and exceptions for online education, text and data mining, and preservation across most countries in the world. Currently, only the text and data mining map is fully implemented, but the maps for online education and preservation will follow soon. The website is available in English, French and Spanish language versions.

We invite you to explore the A2K website and spread the word about the A2K Coalition.

The post Global Civil Society Coalition Promotes Access to Knowledge appeared first on COMMUNIA Association.

Agenda’s ministers iets meer openbaar, maar nogsteeds onvoldoende

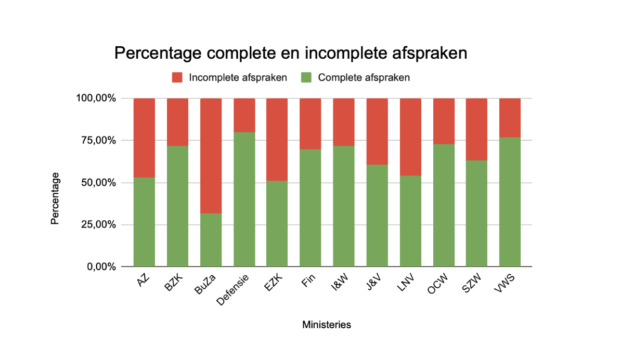

Bijna een jaar geleden stemde een meerderheid in de Kamer voor de motie Sneller-Bromet, waarin gesteld wordt dat de agenda’s van bewindspersonen systematischer bijgehouden moeten worden. Deze motie was een reactie op eerder onderzoek door Open State Foundation, waaruit bleek dat de agenda’s van bewindspersonen verre van transparant zijn. Transparante agenda’s zijn essentieel om inzicht te krijgen in het Nederlandse lobby-landschap en om eventuele belangenverstrengeling aan de kaak te stellen. Hoe staat het er nu voor? Houden bewindspersonen zich aan de richtlijnen, of zijn de agenda’s bijna een jaar na dato nog steeds schimmig?

Hoofdconclusies- Ondanks verbeteringen in de openbare agenda’s van bewindspersonen is lobby nog onvoldoende transparant

- 64% van de afspraken voldoen aan de richtlijnen van de motie Sneller-Bromet en vermeldt onderwerp en contactinformatie. Een duidelijke verbetering, maar veel onderwerpen zijn nietszeggend. De richtlijnen creëren niet genoeg eenduidigheid en dit zorgt voor een lage kwaliteit van de data.

- Bij slechts 43% van de afspraken wordt de gesprekspersoon genoemd

- Grote verschillen tussen ministeries: Buitenlandse Zaken als slechtste, Defensie als beste

- Geen enkel ministerie komt volledig toezegging na dat met terugwerkende kracht agenda’s worden bijgewerkt

In de periode van 25 februari tot 28 september 2022 hebben bewindspersonen in totaal 2.148 gesprekken geregistreerd. Hiervan kunnen 764 worden gedefinieerd als externe gesprekken (met vertegenwoordigers van buiten de overheid).

- 64% van de geregistreerde afspraken voldoet aan de eigen richtlijn dat zowel onderwerp van gesprek als contactgegevens voor verdere informatie moeten zijn vermeld.

- Beste uit de test: Het ministerie van Defensie is het meest succesvol in het correct bijhouden van de agenda’s, waarbij 80% voldoet aan de richtlijnen. Hierbij moet wel gezegd worden dat er slechts 20 externe afspraken te vinden zijn in de openbare agenda’s van het ministerie van Defensie. Onder individuele bewindspersonen komt minister Ernst Kuipers van Volksgezondheid, Welzijn en Sport het beste naar voren: 91% van zijn afspraken zijn compleet.

- Slechtste uit de test: Het Ministerie van Buitenlandse Zaken houdt haar afspraken het slechtst bij, met slechts 32% van de externe afspraken compleet. Door de ministeries van LNV, EZK en AZ worden meer dan 45% van de afspraken niet goed bijgehouden. De afspraken van minister Christianne van der Wal-Zeggelink van Natuur en Stikstof voldoen in meer dan de helft van de gevallen niet aan de richtlijnen (57%), waarmee deze minister het slechtst scoort.

Complete afspraken vermelden zowel een onderwerp als contactpunt voor verdere informatie.

Complete afspraken vermelden zowel een onderwerp als contactpunt voor verdere informatie.

Analyse van de agenda’s

Uit de kwaliteit van de data blijkt dat een cultuurverandering – om door middel van de agenda’s lobby daadwerkelijk beter inzichtelijk te maken – nog ver te zoeken is.

- Daadwerkelijke partij ontbreekt: met wie de bewindspersoon om tafel zit is niet vanzelfsprekend. In plaats van de daadwerkelijke partij te benoemen komt het nog steeds voor dat alleen de sector wordt genoemd, of zelfs alleen “gesprek bedrijven”, zoals in de agenda van Christianne van der Wal-Zeggelink. Minister Van der Wal-Zeggelink behoort tot het ministerie van Landbouw, Natuur en Voedselkwaliteit, een ministerie wat beterschap beloofde na het eerste onderzoek van Open State Foundation, en ook kort verbetering liet zien, maar nu weer terugvalt in zowel de cijfers, als kwaliteit van de data. Het op deze manier bijhouden van externe afspraken is niet bevorderlijk voor transparantie en het inzichtelijk maken wie er invloed heeft op beleid.

- Onderwerp onduidelijk: Sinds de motie van Sneller-Bromet is het verplicht om ook het onderwerp van de gesprekken op te nemen in de agenda’s. Desondanks is de geest van deze motie niet terug te vinden in veel registreerde gesprekken met externen: ‘kennismakingsgesprek’, ‘periodiek gesprek’ of ‘bijpraat gesprek’ zijn termen die herhaaldelijk terugkomen, in plaats van de daadwerkelijke inhoud te delen. Voorbeelden hiervan zijn de agenda’s van staatssecretaris Maarten Van Ooijen en minister Hans Vijlbrief, waarbij het merendeel van de afspraken wordt geregistreerd als ‘kennismakingsgesprekken’, zonder verdere toelichting. Vijlbrief noemt geen één keer een ander onderwerp dan ‘bijpraat/kennismaking’. Dit werkt transparantie in de hand.

- Gebrek aan eenduidigheid: de benaming van partijen wordt niet op een eenduidige manier in de agenda’s opgenomen. Zo gebruikt staatssecretaris Alexandra van Huffelen hoofdzakelijk afkortingen voor de organisaties waarmee ze om de tafel zit en registreert minister Micky Adriaansens een gesprek met Neelie Kroes, zonder te vermelden in welke hoedanigheid mevrouw Kroes aan dat gesprek deelneemt. Dergelijke registraties van afspraken werken transparantie tegen en bemoeilijken de analyse van de agenda’s van bewindspersonen.

Daarom pleit Open State Foundation voor nauwkeurigere richtlijnen voor het bijhouden van de agenda’s. De bestaande regels geven bewindspersonen de ruimte om vaag te blijven over hun gespreksonderwerpen en -partners, waardoor deze richtlijnen slechts schijntransparantie creëren. Om daadwerkelijk transparantie te realiseren, bevelen wij aan:

- Wees concreet over het onderwerp: Bijpraatgesprekken, kennismakingsgesprekken en reguliere gesprekken als onderwerpen geven geen inzicht in wat er besproken wordt. De richtlijn omtrent onderwerp moet dan ook aangescherpt worden.

- Wees duidelijk over de deelnemende partij en persoon: Hierbij moet op z’n minst de partij genoemd worden (bijv. ‘Shell’). Om transparantie te bevorderen en belangenverstrengeling tegen te gaan, zou informatie gegeven moeten worden die te herleiden is tot één persoon (bijv. ‘directeur van Shell’).

- Registreer alle afspraken: daarbij horen ook belafspraken, dit gebeurt tot nu toe niet. Er kan een voorbeeld worden genomen aan minister Robbert Dijkgraaf, die wel belafspraken registreert in zijn agenda.

Alleen als bewindspersonen committeren aan duidelijke richtlijnen die waardevolle informatie waarborgen en ze open zijn tegenover burgers over hun contacten, kan de schimmigheid rond lobby afnemen.

Our proposal for ending geo-blocking of audiovisual works in the EU

Last October, COMMUNIA was invited by the European Commission to a stakeholder dialogue to improve cross border access to audiovisual (AV) content. As part of the stakeholder dialogue, the European Commission organised a series of three meetings during which it invited stakeholders (predominantly organisations representing various parts of the audiovisual media sector) to agree on concrete steps to improve access to and availability of AV content across borders in the EU.

Over these three meetings it became increasingly clear that the majority of the invited stakeholders were not interested in working with the Commission on improving cross border access to audiovisual content in the EU. With the exception of the organisations representing users (apart from COMMUNIA these included BEUC and the Federal Union of European Nationalities) and a few dissident voices within the AV sector the representatives of AV rightholders, distributors, producers and creators insisted that the current system of territorial copyright licensing is working well and that it is essential for the financial sustainability of the European audio-visual sector as a whole.

According to them, the fact that this system also leads to widespread geo-blocking and deprives many Europeans of access to cultural works that are often (at least partially) funded with public money does not justify an intervention in the “well-balanced” business models that underpin AV production in Europe. In addition, they argue that it should be up to the market to increase cross-border access to AV works in the EU (while at the same time lobbying for increased EU support for the production and distribution of AV works).

Request for proposalsAt the beginning of this year — after having been shown the cold shoulder by the AV sector — the Commission put the stakeholder dialogue on hold to reconsider its approach. Then, in June of this year, the Commission sent out a letter to all participants in the stakeholder dialogue inviting them to:

… submit proposals for concrete actions or roadmap presenting the steps you intend to take in order to contribute to improving the online availability and cross-border access to audiovisual works across the EU. We would welcome your proposals for commitments by Friday 23rd September 2022.

Adding that after assessing the proposals received, the Commission would

… convene a final meeting of the dialogue in the autumn in order to formally adopt them as participants’ commitments.

Last week, in response to this invitation, we submitted a proposal for a fallback TVOD service for publicly funded AV works. Here, we develop the concept for an independent not-for-profit platform that would ensure the availability of AV productions – that have received public funding – in all member states of the European Union.

The platform that we are proposing would be a Transactional Video on Demand platform (TVOD – industry parlance for a pay per view platform) and as such would be something that can generate extra revenue for the producers of films made available via the platform. It is not a proposal to make these works available for free.

Our proposal focuses on AV productions that have received public funding — which is the vast majority of AV productions made in Europe — because here the moral and cultural imperatives to make them available across all EU member states is the strongest. Implementing this proposal, which in itself accepts the current practice of exclusive territorial licensing, and — ironically — relies on geo-blocking as a mechanism for this, would be an important step towards a future without structural geo-blocking of AV works that are available in the EU.

We are looking forward to discussing our proposal with other stakeholders in the upcoming meeting of the stakeholder dialogue.

The post Our proposal for ending geo-blocking of audiovisual works in the EU appeared first on COMMUNIA Association.

Walled Culture, the Book, Now Available

‘Walled Culture: How Big Content Uses Technology and the Law to Lock Down Culture and Keep Creators Poor’ is a new book by long time tech journalist and copyright policy observer Glyn Moody.

The book is available as a paperback and for download in various digital formats. It is part of the Walled Culture Project and provides a compact, non-technical history of digital copyright and its problems over the last 30 years, and the social, economic and technological implications. One chapter chronicles the fight over the EU copyright directive between 2014 and 2019.

Glyn who has been a keen observer of all discussions around copyright policy in the EU over the past decades tries to answer the following key questions:

- What are the problems with copyright in the digital age?

- Why does copyright harm creators and block global access to knowledge?

- How does copyright threaten basic freedoms and undermine the Internet?

- How can we promote creativity and help artists and make a living in the digital age?

- What should we do to solve all these problems?

Walled Culture draws on the interviews published on the project website. All references to online sources link to archival copies held by the Internet Archive, thus ensuring that the book will remain useful even when the original sources are relocated or become permanently unavailable.

COMMUNIA congratulates Glyn on the publication of his important book and particularly on his choice to dedicate the book to the Public Domain.

The post Walled Culture, the Book, Now Available appeared first on COMMUNIA Association.

Kamerleden erkennen belang van integriteit-wetgeving, maar weg ernaartoe lijkt nog lang

Het vertrouwen in de politiek is enorm laag, zo wijst een nieuw Ipsos-onderzoek uit. Recente integriteitsschandalen, zoals de overstap van minister Cora van Nieuwenhuizen naar een lobbyclub, hebben hieraan bijgedragen. Het waarborgen van de integriteit van bewindspersonen stond op 19 september centraal tijdens een Kameroverleg over de initiatiefnota van Laurens Dassen (Volt) en Pieter Omtzigt (Groep Omtzigt). Kamerleden discussieerden over het belang van openbare agenda’s, een lobbyregister en vielen over de definitie van ‘lobbyist’.

Op 19 september besprak de Tweede Kamer commissie Binnenlandse Zaken de initiatiefnota van Dassen en Omtzigt ‘over wettelijke maatregelen om de integriteit bij bewindspersonen en de ambtelijke top te bevorderen’. Dassen en Omtzigt hadden deze initiatiefnota in mei 2022 naar buiten gebracht in reactie op een rapport van corruptie waakhond Greco en onderzoeken van Open State Foundation omtrent de politieke draaideur en de agenda’s van bewindspersonen.

Over het belang van dit onderwerp en de noodzaak tot actie bestond geen twijfel onder de aanwezige Kamerleden. Sommigen noemden de reactie van de minister Hanke Bruins Slot van Binnenlandse Zaken en Koninkrijksrelaties op de initiatiefnota vrijblijvend en bekrachtigden de ambitie van de nota om de regelgeving omtrent integriteit een wettelijke basis te geven. Toch hadden een aantal Kamerleden ook hun bedenkingen bij bepaalde aspecten van de nota.

Vooral rondom het lobbyregister werden obstakels gezien: Commissieleden Renske Leijten (SP), Caroline Van der Plas (BBB) en Joost Sneller (D66) zagen het lastig definiëren van het begrip ‘lobbyist’ als belemmering voor het invoeren van een register, en vroegen daarom de initiatiefnemers duidelijkheid te scheppen over dit begrip. Ook minister Hanke Bruins Slot van Binnenlandse Zaken en Koninkrijksrelaties vond de definitie onduidelijk, en laat het onderzoeken door hoogleraar Caelesta Braun van Universiteit Leiden. Dassen had echter een helder antwoord: iedereen –ongeacht achtergrond– die politici en bestuurders benadert om beleid te beïnvloeden is een lobbyist. De discussie rondom de definitie van ‘lobby’ lijkt inderdaad onnodig: andere landen, de Raad van Europa en OESO hebben dit begrip al gedefinieerd. Marieke Koekkoek (Volt) stelde dat het vooral gaat om transparantie: Het moet te traceren zijn wie invloed heeft gehad op beleid. Open State Foundation deelt deze benadering. Het streven naar transparantie moet centraal staan.

Ook het uitwerken van het lobbyregister en openbare agenda’s was onderwerp van discussie. Sneller stelde dat Nederlandse Kamerleden niet de middelen hebben om hun afspraken en contacten bij te houden en openbaar te maken. Koekkoek merkte hierbij op dat landen zoals Ierland, Canada en de VS wel succesvol gebruik maken van lobbyregisters en openbare agenda’s. Leijten voegde toe dat het essentieel is dat agenda’s openbaar worden gemaakt, ook voor Kamerleden. Open State deelt de overtuiging dat Kamerleden meegenomen moeten worden in het integriteitsbeleid, want ook zij worden belobbyd. Sneller en Leijten spraken af om voor een bepaalde tijd te experimenteren met het openbaar maken van hun agenda’s om te onderzoeken of dit daadwerkelijk meer ondersteuning vraagt. Een goed initiatief!

In hun beantwoording van de vragen onderstreepten de initiatiefnemers het belang van het wettelijk onderbouwen van de regelgeving omtrent integriteit. Zo herhaalde Dassen dat wettelijke kaders transparantie bevorderen, en constateerde Omtzigt dat recente incidenten rondom integriteit het belang van een wettelijke basis voor integriteitsregels benadrukken. Ook stelde Omtzigt dat nu actie ondernomen moet worden: “We moeten nu doorpakken in plaats van telkens weer advies te vragen.” Open State zou eveneens meer doortastendheid willen zien van de minister en de Kamer in het wettelijk onderbouwen van integriteitsregels.

Ook de minister was zich bewust van de urgentie die de initiatiefnemers, Kamerleden en maatschappelijke organisaties verwoorden rondom dit onderwerp. Ze erkende het belang van het creëren van een wettelijke basis voor integriteit-regelgeving en transparantie. Dat het streven naar transparantie nog niet helemaal ingebakken zit in haar eigen ministerie bleek uit een bijna volledig zwartgelakte beslisnota die Kamerleden voorafgaand aan de Commissievergadering kregen. Vragen over hoe dit heeft kunnen gebeuren kon de minister niet overtuigend beantwoorden, en ze beloofde er op terug te komen tijdens de tweede termijn.

De eerste termijn van de Commissievergadering over regelgeving omtrent integriteit bewindspersonen liet zien dat iedereen het eens is over het belang van het onderwerp, maar dat er tegelijkertijd bezwaren zijn die het doorpakken bemoeilijken. Open State Foundation is van mening dat het blijven hangen in de discussie over de definitie van ‘lobbyist’ het debat onnodig vertraagt, en dat de focus moet liggen op het streven naar transparantie. Zoals Pieter Omtzigt stelde: misschien is dit niet perfect, maar het is in ieder geval een goede stap en het zal zich verder ontwikkelen. Nu niets doen en wachten op het zoveelste onderzoek of het uitpluizen van een definitie: dat is niet waar Nederland en Greco op zitten te wachten.

COMMUNIA Receives Eight-Year Grant from Arcadia

The International Association on the Public Domain looks to expand its advocacy work and engage in strategic litigation in Europe.

COMMUNIA has been awarded an eight-year grant of three million euros by Arcadia – a charitable fund of Lisbet Rausing and Peter Baldwin. This opens a new chapter in the history of the organisation, which was founded in 2011 as an EU thematic network and has been one of the most active civil society organisations on European copyright reform in recent years.

Arcadia’s open access programme supports work that improves access to human knowledge and helps make information free for anyone. With Arcadia’s generous support, COMMUNIA will expand its policy work for copyright reform and initiate strategic litigation, aiming to establish itself as the principal advocacy organisation for the Public Domain in Europe.

Portuguese copyright expert Teresa Nobre and German access to knowledge activist Justus Dreyling are joining COMMUNIA as co-directors to advance COMMUNIA’s mission and organisational development.

“We have witnessed decades of narrowing of the Public Domain through the expansion of the scope of copyright protection and the creation of new exclusive rights. It is time to reverse this trend. To achieve this goal, we are committed to making COMMUNIA an even stronger voice for the Public Domain in policy debates in Europe and beyond,” says COMMUNIA’s incoming Policy Director Justus Dreyling.

COMMUNIA’s advocacy work is based on a set of 20 policy recommendations, which were launched in May of this year. In the future, COMMUNIA will also defend the Public Domain and usage rights in court through strategic litigation.

“The public domain belongs to all and is often defended by no-one. We want to change that. COMMUNIA wants to play a new role in reshaping copyright and defending the public domain from misappropriation. We are prepared to make our vision a reality through advocacy and judicial means,” explains Legal Director Teresa Nobre.

About Arcadia

Arcadia is a charitable fund of Lisbet Rausing and Peter Baldwin. It supports charities and scholarly institutions that preserve cultural heritage and the environment. Arcadia also supports projects that promote open access and all of its awards are granted on the condition that any materials produced are made available for free online. Since 2002, Arcadia has awarded more than $910 million to projects around the world.

The post COMMUNIA Receives Eight-Year Grant from Arcadia appeared first on COMMUNIA Association.

The European Roots of Controlled Digital Lending

Libraries have long played a crucial role in ensuring broad public access to knowledge and culture. So as more and more of our lives take place online, it is important that libraries are able to play their traditional role there. This concept is at the heart of our Policy Recommendation #10: libraries should be enabled to fulfil their mission in the digital environment.

In order for libraries to do so, they need to be able to perform their usual functions–such as the preservation and lending of books and other materials–digitally. One way to do that is through controlled digital lending (CDL). With CDL, libraries own–rather than licence–digital copies of their collections, so they can preserve them in digital format and lend them to their patrons online. Of course, any such lending must be controlled: libraries can only lend as many digital copies as they have bought and paid for (such as by buying and digitising a physical copy), and they must take steps to ensure that this 1:1 lending restriction is controlled by digital means (generally, by using digital rights management). But with these controls in place, CDL is the digital equivalent of traditional library lending; nothing more, nothing less.

Many of the world’s largest publishers are opposed to CDL, and have recently attacked it–such as in their lawsuit against Internet Archive in the United States–as a legal theory “manufacture[d]” in the US “[a]round 2018.” That is not correct. In fact, while the term “controlled digital lending” may be of more recent vintage, this kind of “eLending” has deep roots in European law and practice.

While rental and lending rights are not established in the United States or many other countries, such rights have been a feature of European Union law since 1992. And they were a part of various member state laws for decades prior–by some accounts, they have been under discussion in Europe for over one hundred years. Over this time, careful and sustained attention has been given throughout Europe to the rights of libraries, authors, publishers, and the public. This attention has been manifested in a variety of legislative approaches to public lending over a series of decades, and it has continued into the modern era, as the original rental and lending directive was updated in 2006, and its application to the digital environment was repeatedly examined by the Court of Justice of the European Union. As a result, one should not be surprised to find that the law and policy of library lending in Europe has been carefully considered and refined–including with respect to digital lending practices like CDL.