U bent hier

Onlife - Floridi

I just published "On asking the wrong kind of questions (series: notes to myself)", happy 2024. https://link.medium.com/thDMgqTvZFb Onlife - Luciano Floridi's blog

I just published "On asking the wrong kind of questions (series: notes to myself)", happy 2024. https://link.medium.com/thDMgqTvZFb

Onlife - Luciano Floridi's blogOn a sachet of brown sugar (series: notes to myself)

Mid-morning, somewhere in Italy. Seating at a bar, in an elegant square, summery weather, a kind breeze, refreshing. An espresso macchiato comes with a brown sachet of sugar, to be added if you wish. I look at it. I look around. I have time to think. How do people deal with this task? Can one divide people, the sugary kind, into types according to how they open a sachet of sugar?

Mid-morning, somewhere in Italy. Seating at a bar, in an elegant square, summery weather, a kind breeze, refreshing. An espresso macchiato comes with a brown sachet of sugar, to be added if you wish. I look at it. I look around. I have time to think. How do people deal with this task? Can one divide people, the sugary kind, into types according to how they open a sachet of sugar?A student, with interesting tattoos on her left shoulder, opens it by pinching the two sides and pulling them, gently ungluing the sachet. It requires her to use four fingers, each couple pinching a side of the sachet. She is attentive and careful. She better be. I know that feat is demanding. Too much force and the sachet may give in abruptly, spreading the sugar everywhere. Too little, and the little shell will hold on to its content and won’t be convinced to release its treasure. I love the cautions determination. She puts her hands together, palms touching at the bottom as if praying, to measure the effort more gradually. She succeeds. I’m not sure it is a smile, but now the tattoo, which seems like a tiger from here, is moving forward, to sweeten the cappuccino. She is left-handed. The sachet is no longer the focus of her attention. The whirlpool created by the spoon is. The sachet will be nothing but a small, open, and empty envelop that can be easily disposed of. A brown shell, once full of granular nutrients, itself made of something that was alive in the past. Life, containing life, adding itself to life, to be absorbed by life. I wonder how far that piece of paper has travelled, how distant the soil that hosted the roots of the tree from which it came. Printed, manufactured in millions of clones, indistinguishable from all the others and now with its internal body visible, exposed, ready to be filled by air, or some dust. She irons the sachet distractedly and places it under the little glass of water she had duly drunk before her coffee. Sparkling, if it is like mine. The water left in it cannot touch the paper of the sachet, the two separated by a transparency that slightly enlarges the letter of the manufacturing company.

The careful exercise by the girl with a tiger takes a serious effort, but it pays back in terms of elegance, efficiency, and simplicity of the solution. A sort of Ockham’s razor that does not multiply the entities. This is not the case with the busy, middle-aged man who tears the top of the sachet. He does not seem in a hurry, and yet the gesture is firm, rapid, unquestioning, and straightforward. One single movement of his right hand, while the left holds the victim to be decapitated, as surgically precise and painlessly as possible. He just ended a call, and is now concentrating on his coffee. Maybe it is a habit, the decisive gesture of a problem-solver who has cut more than a Gordian knot in his life. A stereotype, I know, but he does have that look. Maybe the suit, or perhaps how he calmly but firmly explained the agenda to someone over the phone. Someone not to mess with. And yet, his attitude has just created a problem. For he now finds himself with two pieces of paper. A head and a body. He may not care, and leave them flying around, courtesy of the breeze. A Robespierre who will have other victims in sight. But I see that it bothers him to be untidy in his solution. He must complete the operation. I anticipate that he will simply reunite them through a violent operation of folding or crushing, the broken wholeness unfixable, if not merely in appearance. But no. I was wrong. He has a more careful and engineering approach. He takes his time to pick up the small top strip, now dethatched, to insert it meticulously inside the larger, open sachet, now empty, producing an artefact that now contains itself. The empty sachet now includes a piece of itself, and can be disposed of as a different kind of whole, neatly folded twice, next to the spoon. A problem solved with some expenditure of resources, but in no less elegant way than that adopted by the girl. I stand corrected. The decision-maker is also attentive to details. He likes to see things through. The two detached pieces won’t fly away in the sunny square, parting like a leaf on a wintery day.

The waitress has just delivered the material for one more experiment. I’m not disappointed. I’m looking for a kindred soul. Not someone who preserves the whole. Not someone who decapitates the sachet. But you, who partially tear the sachet just enough, inflicting only the necessary pain, a cut that must be imposed for the sugar to become available, long enough, yet not complete, so that the partially detached top is not independent. An inch, or less, to ensure no sugar leaves the sachet (who in their right mind ever tears a sachet in the middle?) two-thirds or at most four fifth (but I do not recommend it, for it is too risky!) tear, obtained, if you have time, by first folding in a straight line the part to be partially removed. A compromise, to ensure that the whole remains intact, even if now its semi-detached piece holds on to the rest by a small proportion of its length. The man, now performing the trick, can do that efficiently, three sachets at a time. He has trained for decades. And his image looks familiar, reflected by the glass of the bar.

------

"Notes to myself" is available as a book on Amazon: ow.ly/sGyh50KfRra

Photo by Rachel Claire: https://www.pexels.com/photo/mug-of-coffee-on-wooden-table-4577860/

Onlife - Luciano Floridi's blog

Sulla morte come "distanza che si apre nella vita"

“La morte è una distanza che si apre nella vita, ma non è sparizione, distruzione, putrefazione.”

“La morte è una distanza che si apre nella vita, ma non è sparizione, distruzione, putrefazione.”Ho letto questa frase (chiamiamola non-P), è l’inizio di un articolo giornalistico (non si può imporre un rigore scientifico, non è il contesto). Ho letto il resto dell’articolo. Non migliora. Non ha importanza. Desidero soffermarmi solo questa frase.

Da tanti anni non sono più un filosofo analitico, ma mi è rimasta l’inclinazione (il vizio senza pelo del lupo?) di (cercare di) usare le parole con attenzione e cura. Cercando di ancorarle a significati che non siano “futuristici” (parole in libertà). Troppe persone confondono il fatto che una frase sia grammaticale con il fatto che abbia un reale senso. Si può anche dire:

P) “La morte non è una distanza che si apre nella vita, è sparizione, distruzione, putrefazione.”

P è altrettanto grammaticale e credo che abbia molto più senso di non-P, almeno biologicamente e concettualmente. I fatti puntano in questa direzione. E chi sostiene il contrario, chi sostiene non-P, ha sulle sue spalle il peso della prova, non chi sostiene P. Perciò non dovrebbe spacciarla come qualcosa di incontrovertibile. Ma torniamo alla frase originale.

Ora, che cosa può significare in non-P che la morte è una distanza (tra chi o che cosa) che si apre (una volta sola, come un spacco? Oppure continua ad aprirsi sempre di più, come una faglia?) in uno spazio chiamato vita? Se stiamo dicendo che è una distanza tra noi, vivi, e loro, morti, allora basta dirlo così, capendoci subito. È una banalità un po’ retorica ma è chiara ed è plausibile . Via via che passa il tempo la morte di mamma è una “distanza” nella “vita”. Insomma: la vita passa e sono sempre più anni che mamma è morta. Grazie al cavolo, ma vero. Ma se è una distanza NELLA vita, cioè al suo interno, uno sta assumendo che di qua e di la c’è la vita. Come una spaccatura nel legno, fissa o dinamica che sia, è NEL legno, che la caratterizza proprio come una sua spaccatura. E qui sta il passo implicito e silenzioso di chi fa assunzioni immense, senza giustificarle. Perché, per quanto ne sappiamo, la frase (non-P) o non ha senso, oppure è falsa. La morte è dove finisce il legno, non è una spaccatura nel legno, per capirsi. È assenza completa della vita, non è - per quanto ne sappiamo - un buco per strada, basta saltarlo (riferimento voluto al salto della fede) tanto dall’altra parte c’è il marciapiede. Mi si dirà: ma io CREDO che sia così. Ottimo. Allora dillo come va detto: credo che la morte sia una mancanza tra una vita mortale e una immortale, di qua e di là. A me pare una bellissima favola. Un tempo ci credevo anche io e darei qualsiasi cosa (nessuna retorica) per crederci di nuovo. Ma soprattutto si capisce, il punto è chiaro, anche se temo che sia, per persone come me, incredibile nel senso etimologico della parola. Chi ci crede e chi non ci crede. Non è un fatto, non è un verità, non è neppure una cosa plausibile, o probabile, o sulla quale c'è notevole accordo. È una cosa che andrebbe detta con un condizionale tipo "Io credo che". A questo punto subentra la libertà di fede, di dubbio e di certezze molto diverse … ciascuno può credere quello che vuole, e vivere la sua vita secondo le credenze che ha, ci mancherebbe. Senza però asserirle con quel tono apodittico, che è solo ridicolo e vuole impressionare con trucchi retorici. Il resto è brutta scrittura, intellettualmente oscura e fuorviante. Piace giustamente a chi ha già la fede, che la morte sia solo “una distanza che si apre”, qualsiasi cosa questa frase possa mai significare realmente. Ma rispetto molto di più chi dice con chiarezza: “credo nella resurrezione dei morti”. Ora ci capiamo. e sopratutto sappiamo chi ha l'onere di convincere chi.

Parlare per dire cose che hanno significato, non per vendere credenze (beliefs) sottobanco senza che il compratore se ne accorga. Sarebbe già un passo avanti.Onlife - Luciano Floridi's blog

Onlife: Sulla morte di Corman McCarthy e "the best writers" della letteratura americana

Corman McCarthy è stato descritto da alcuni come il più grande scrittore americano di [aggiungere qui un numero di secoli, oppure "la nostra epoca", oppure "una generazione" o semplicemente "sempre"]. Siccome sono insipiente, e lo avevo solo sentito nominare ma mai letto (ma i mie amici come mai non me lo hanno mai consigliato? che ci stanno a fare? O almeno Amazon, visto il numero di libri che compro, un "you may also like" lo poteva sputare no?), sono andato a vedere chi fosse. Ho letto un po' di cose su di lui, tutte molto interessanti. E poi mi sono chiesto chi rientra oggi in una lista più o meno accurata degli scrittori americani più importante degli ultimi 100 anni. Insomma, se uno dice, per esempio, "è morto il più grande scrittore americano del secolo" ti viene il dubbio di ricostruire la competizione gli ultimi cento anni.

Corman McCarthy è stato descritto da alcuni come il più grande scrittore americano di [aggiungere qui un numero di secoli, oppure "la nostra epoca", oppure "una generazione" o semplicemente "sempre"]. Siccome sono insipiente, e lo avevo solo sentito nominare ma mai letto (ma i mie amici come mai non me lo hanno mai consigliato? che ci stanno a fare? O almeno Amazon, visto il numero di libri che compro, un "you may also like" lo poteva sputare no?), sono andato a vedere chi fosse. Ho letto un po' di cose su di lui, tutte molto interessanti. E poi mi sono chiesto chi rientra oggi in una lista più o meno accurata degli scrittori americani più importante degli ultimi 100 anni. Insomma, se uno dice, per esempio, "è morto il più grande scrittore americano del secolo" ti viene il dubbio di ricostruire la competizione gli ultimi cento anni.Le posizioni sono ovviamente e come sempre discutibili, ma mi è stato utile ricordare a chi si sta confrontando McCarthy, magari per confermare un giudizio letto, oppure rivederlo del tutto, a propria scelta, dato che tutto ciò rientra nei gusti personali.

Per pigrizia e incompetenza metto la lista stilata da ChatGPT (che ogni tanto si rende utile) alla domanda: chi sono i più grandi autori americani degli ultimi cento anni (ho pensato che "di sempre" fosse un po' troppo, ma vedi sotto per questa lista).

Ecco i primi dieci (prompt: best 10 American writers of past 100 years):

1) Ernest Hemingway (1899-1961) - Known for his concise and powerful writing style, Hemingway's works include "The Old Man and the Sea" and "For Whom the Bell Tolls."

2) F. Scott Fitzgerald (1896-1940) - His novel "The Great Gatsby" is considered a classic of American literature, capturing the Jazz Age and the disillusionment of the American Dream.

3) Toni Morrison (1931-2019) - An important voice in African American literature, Morrison's novels, such as "Beloved" and "Song of Solomon," explore themes of race, identity, and history.

4) William Faulkner (1897-1962) - Faulkner's experimental and complex writing style is evident in novels like "The Sound and the Fury" and "As I Lay Dying," which explore the Southern Gothic tradition.

5) Harper Lee (1926-2016) - Lee's Pulitzer Prize-winning novel "To Kill a Mockingbird" is a powerful exploration of racial injustice and childhood innocence.

6) J.D. Salinger (1919-2010) - Salinger's novel "The Catcher in the Rye" became an influential coming-of-age story and has resonated with generations of readers.

7) Flannery O'Connor (1925-1964) - Known for her Southern Gothic style, O'Connor's short stories, such as "A Good Man Is Hard to Find," delve into themes of morality, religion, and human nature.

8) John Steinbeck (1902-1968) - Steinbeck's works, including "The Grapes of Wrath" and "Of Mice and Men," often portray the struggles of the working class and examine social and economic issues.

9) Saul Bellow (1915-2005) - Bellow's novels, such as "The Adventures of Augie March" and "Herzog," explore themes of identity, Jewish-American culture, and the complexities of modern life.

10) James Baldwin (1924-1987) - Baldwin's essays and novels, like "Go Tell It on the Mountain" and "The Fire Next Time," confront issues of race, sexuality, and social injustice in America.

Tutti famosi e per fortuna letti... Ma mi sembrava che manchessero altri nomi altrettanto famosi, perciò ho chiesto a ChatGPT di elencare i dieci successivi:

11) Kurt Vonnegut (1922-2007) - Vonnegut's satirical novels, such as "Slaughterhouse-Five" and "Cat's Cradle," blend science fiction with social commentary.

12) Maya Angelou (1928-2014) - An acclaimed poet, memoirist, and civil rights activist, Angelou's works include "I Know Why the Caged Bird Sings" and "And Still I Rise."

13) David Foster Wallace (1962-2008) - Wallace's novel "Infinite Jest" is often regarded as a seminal work of postmodern literature, known for its complexity and exploration of contemporary society.

14) Zora Neale Hurston (1891-1960) - Hurston's novel "Their Eyes Were Watching God" is considered a classic of African American literature, showcasing the experiences of black women in the early 20th century.

15) Ralph Ellison (1913-1994) - Ellison's novel "Invisible Man" explores themes of race, identity, and the search for self in America.

16) Sylvia Plath (1932-1963) - Plath's poetry, including her collection "Ariel," is known for its confessional style and powerful exploration of mental health and femininity.

17) Philip Roth (1933-2018) - Roth's novels, such as "American Pastoral" and "Portnoy's Complaint," often depict the complexities of American identity and Jewish-American culture.

18) Flannery O'Connor (1925-1964) - O'Connor's works, including her short story collection "Everything That Rises Must Converge," are known for their dark humor and exploration of the human condition.

19) Annie Proulx (born 1935) - Proulx's novel "The Shipping News" won the Pulitzer Prize and her short story "Brokeback Mountain" was adapted into an acclaimed film.

20) Denis Johnson (1949-2017) - Johnson's novels, such as "Tree of Smoke" and "Jesus' Son," often depict characters on the fringes of society and explore themes of addiction, redemption, and spirituality.

Qui già passo male l'esame, alcuni e alcune non li conosco affatto... altro che non letti. Ma ancora nessuna traccia di Cormac McCarthy, quindi ho chiesto altri dieci ancora, per arrivare ai primi 30 ed ecco comparire il nostro autore:

21) Wallace Stevens (1879-1955) - Stevens was a renowned poet known for his richly imaginative and philosophical works, including "Harmonium" and "The Collected Poems of Wallace Stevens."

22) Allen Ginsberg (1926-1997) - Ginsberg was a leading figure of the Beat Generation and his poem "Howl" is considered a defining work of the era.

23) Eudora Welty (1909-2001) - Welty's short stories, including "A Worn Path" and "The Optimist's Daughter," capture the essence of the American South and explore themes of family, race, and memory.

24) Thomas Pynchon (born 1937) - Pynchon's complex and postmodern novels, such as "Gravity's Rainbow" and "The Crying of Lot 49," challenge traditional narrative structures and often delve into themes of paranoia and power.

25) Louise Erdrich (born 1954) - Erdrich, an acclaimed Native American writer, has written novels like "Love Medicine" and "The Round House," which explore Native American culture, history, and identity.

26) Raymond Carver (1938-1988) - Carver's short stories, including those in the collection "What We Talk About When We Talk About Love," are known for their minimalistic style and exploration of ordinary lives.

27) Don DeLillo (born 1936) - DeLillo's novels, such as "White Noise" and "Underworld," often tackle themes of consumerism, media, and the anxieties of modern society.

28) Toni Cade Bambara (1939-1995) - Bambara was a prominent African American writer known for her short story collection "Gorilla, My Love" and her commitment to social activism.

29) Cormac McCarthy (born 1933) - McCarthy's novels, including "Blood Meridian" and "The Road," often explore themes of violence, nature, and human morality.

30) Elizabeth Bishop (1911-1979) - Bishop was a highly regarded poet known for her precise language and attention to detail. Her notable works include "North & South" and "Geography III."

Fine dell'esperimento. De gustibus, of course. E poi ChatGPT riassume solo la vox populi (poi dicono che il Classico non serve, e da dove viene tutto questo latinorum...). L'intera lista include alcuni autori e alcune autrici di cui non ho mai sentito parlare (e devo anche controllare se ChatGPT ha inventato qualche dato) ... sarà bene che inizi a documentarmi e leggere più narrativa americana... per stilare la mia personale in modo meno disinformato.

PSIo per ora farei solo una correzione: al n. 10, nella mia lista personale, metterei Kurt Vonnegut e con i primi 10 sarei già felice.

PS Prima che mi arrivi una sgridata, lo so che le risposte cambiano a seconda del prompt, ecco che succede, per esempio, se uno chiede (prompt): who are the 100 most important american writers of all time? Cormac McCarthy è 64esimo. Sempre ChatGPT docet (ah, l'utilità del Classico). Mi dispiace per Jack London.

- Mark Twain

- Edgar Allan Poe

- Herman Melville

- Emily Dickinson

- F. Scott Fitzgerald

- Ernest Hemingway

- William Faulkner

- Ralph Waldo Emerson

- Henry David Thoreau

- Walt Whitman

- Nathaniel Hawthorne

- Toni Morrison

- Harper Lee

- John Steinbeck

- T.S. Eliot

- Langston Hughes

- Zora Neale Hurston

- James Baldwin

- Sylvia Plath

- Flannery O'Connor

- William Faulkner

- Saul Bellow

- Philip Roth

- James Fenimore Cooper

- John Updike

- Thomas Pynchon

- Emily Brontë (though British, her work has had a significant impact on American literature)

- J.D. Salinger

- Wallace Stevens

- Allen Ginsberg

- Ralph Ellison

- Robert Frost

- Maya Angelou

- Anne Bradstreet

- William Carlos Williams

- Herman Wouk

- Gore Vidal

- Truman Capote

- Edith Wharton

- Willa Cather

- Ralph Waldo Emerson

- Henry James

- Tennessee Williams

- Richard Wright

- Margaret Atwood (though Canadian, her work has had a significant impact on American literature)

- Jack Kerouac

- James Joyce (though Irish, his work has had a significant impact on American literature)

- Sandra Cisneros

- Don DeLillo

- Louise Erdrich

- Thomas Jefferson

- James Agee

- Eudora Welty

- Frederick Douglass

- Kurt Vonnegut

- Octavia Butler

- Harriet Beecher Stowe

- Sinclair Lewis

- Ralph Waldo Emerson

- Allen Tate

- Adrienne Rich

- John Dos Passos

- Amy Tan

- Cormac McCarthy

- Richard Yates

- James Dickey

- John Berryman

- Elizabeth Bishop

- Jhumpa Lahiri

- Raymond Carver

- Henry Roth

- Jack London

- Kate Chopin

- Djuna Barnes

- Richard Ford

- Carson McCullers

- Nella Larsen

- John Ashbery

- Kurt Andersen

- Jonathan Franzen

- Charles Bukowski

- Joyce Carol Oates

- August Wilson

- Alice Walker

- William S. Burroughs

- Bernard Malamud

- Jonathan Swift (though Irish, his work has had a significant impact on American literature)

- Nathanael West

- Sherman Alexie

- Leslie Marmon Silko

- Richard Russo

- John Cheever

- Theodore Dreiser

- Philip K. Dick

- Gary Snyder

- Anaïs Nin

- Robert Penn Warren

- Paul Auster

- Adrienne Kennedy

- Amiri Baraka

Breve commento su "Non è il mio lutto" e la morte di Berlusconi.

Ho sempre criticato Berlusconi, i suoi votanti, il suo partito, il berlusconismo, gli italoforzuti, i suoi governi, la tragedia (soprattutto morale, ma anche istituzionale, politica, culturale ed economica) che tutto ciò è stato per il paese... Berlusconi è stato un disastro per l'Italia, una sorta di Trump al potere o vicino al potere per decenni. Servirà moltissimo lavoro e tanto tempo per riparare i danni fatti, ammesso che si possano riparare.

Ho sempre criticato Berlusconi, i suoi votanti, il suo partito, il berlusconismo, gli italoforzuti, i suoi governi, la tragedia (soprattutto morale, ma anche istituzionale, politica, culturale ed economica) che tutto ciò è stato per il paese... Berlusconi è stato un disastro per l'Italia, una sorta di Trump al potere o vicino al potere per decenni. Servirà moltissimo lavoro e tanto tempo per riparare i danni fatti, ammesso che si possano riparare. Ma Mercoledì 14 Giugno ho spostato la lezione del corso che tengo a Bologna, affinché chi volesse potesse participare ai funerali di stato e commemorare la morte di Berlusconi, e perché l'attuale governo ha proclamato il lutto nazionale per un politico che (con mio scandalo e vergogna) è stato eletto democraticamente da milioni di italiani e italiane (che gli dei dell'Olimpo li perdonino, io non ci riesco, e posso solo rispettarne le scelte), e ha ricoperto la carica di primo ministro quattro volte.

Non è stata una forma di rispetto verso l'uomo, che non ne meritava alcuno, o verso la figura politica, imbarazzante e giustamente criticabile. È stata una forma di resistenza. Non volevo concedere a Berlusconi l'ultima parola. Perché una cosa che Berlusconi non dovrebbe riuscire a fare, neppure da morto, è ridurci come lui, del tutto privi di valori, senza alcun senso dello stato, senza rispetto neppure per la morte e per il dolore altrui, incentrati solo su noi stessi, i nostri vantaggi e svantaggi, il nostro interesse, la nostra convenienza, i nostri pruriti, desideri, ambizioni, il nostro chiederci sempre, comunque e soltanto se qualcosa sia o non sia MIO, anche un lutto nazionale.

Come ha detto un amico: il danno lo aveva già fatto, c'è poco da rallegrarsi. Come ho detto per anni: l'Italia si libererà di Berlusconi solo biologicamente, come la Spagna ha fatto con Franco. Come previsto, gli italiani e le italiane lo hanno votato fino all'ultimo giorno. Alla fine ci si è liberati di questo scandalo politico solo con la sua morte. Resta il dispiacere per coloro che sono addolorati - "I have suffered with those that I saw suffer", The Tempest, insegna questa civiltà, da esercitare in questo caso anche verso gli incivili come Berlusconi - e soprattutto il profondo dolore per il fatto che il berlusconismo precede Berlusconi e gli sopravvive. Chi si illude che morirà con lui ha una visione meramente burocratico-istituzionale della cultura politica. Berlusconi ha solo incarnato meglio di chiunque altro il berlusconismo, lo ha ipostatizzato, si direbbe in filosofia, metastatizzato, si direbbe in medicina, in un' Italia che di sua natura è da sempre più berlusconiana che fascista, o comunista, o democratica, o liberale, o conservatrice. La questione è se il berlusconismo tornerà a sciogliersi come un veleno sempre presente nella cultura del paese - come mi auguro - o tornerà ad aggrumarsi in qualche altra figura che abbia lo straordinario vuoto morale di farsene contenitore e promotore. C'è da sperare, perché il vuoto morale, come quello fisico, è raro, e le circostante affinché abbia successo sono eccezionali. Aggettivi come "unico", "irripetibile", "insostituibile" usati in questi giorni suggeriscono a persone come me che forse il peggio è passato e che uno come Berlusconi non ricapiterà mai più, ma meglio stare in guardia.

PS L'italiano non è la mia lingua, ma la lingua della comunità alla quale appartengo, volente o nolente. Il lutto nazionale non è il mio lutto, ovviamente, perché è quello della nazione in cui sono nato e dalla quale sono emigrato anche a causa del suo berlusconismo, insopportabile. L'unico vero modo di ribellarsi non è negare l'appartenenza storica - gesto retorico inutile, facile e non molto civile di fronte alla morte di una persona - ma cambiare eticamente la natura di quello al quale si appartiene. Sforzandosi di pensare meglio, comunicare meglio, votare meglio, agire meglio, e di dare il buon esempio, per quanto sia possibile. Tutte cose difficili, tanto quanto raggiungere il vuoto morale di un Berlusconi. Ma necessarie, affinché il dover essere prevalga sull'essere sbagliato.

On the house left behind by a travelling God (series: notes to myself)

There are some famous parables in the New Testament in which people travel, arrive, go away, or come back (for example, Matthew 25:1-13 on the ten virgins; Luke 15:11-32 on the prodigal son). But I have one in mind that has puzzled me for a long time: Matthew 25:14-15 (on the talents), about the man, probably representing God, who is “going on a journey” (ἀποδημῶν) and “comes back after a long time” (πολὺν χρόνον).

There are some famous parables in the New Testament in which people travel, arrive, go away, or come back (for example, Matthew 25:1-13 on the ten virgins; Luke 15:11-32 on the prodigal son). But I have one in mind that has puzzled me for a long time: Matthew 25:14-15 (on the talents), about the man, probably representing God, who is “going on a journey” (ἀποδημῶν) and “comes back after a long time” (πολὺν χρόνον). The word ἀποδημῶν means “about to go on a journey”, and it is the same word used in another parable, when God goes away, again (Matthew 21:33-46). In both cases, he leaves the house for reasons that are not provided. Why does he have to go? Can he not stay? It seems that more pressing business calls him elsewhere. Something or someone is more important than us, who live in the house. An emergency? Or perhaps just a test? Maybe he just wants to see what the mice do when the cat is away. Whatever the motives, there is a journey, a time before and after his presence, and then the long time of his absence, that πολὺν χρόνον. And a house left behind.

God’s absence has consequences, as one should expect. God becomes a past memory, for those who were with him before he left, and a future expectation, for those who believe that he is coming back. The parable speaks of a prolonged (πολὺν is a lot of time) but not a permanent absence. And it cannot be that long because the people who saw him leaving are the same ones who welcome him back. But what if God were to come back much, much later? Not days, weeks, months, or even years, but decades later? What if his absence is sine die? What would happen to the people left behind?

A new generation may grow up knowing only the reports of those who knew him. The grandchildren of the servants, who inherited the house, may become doubtful. They never met him, never saw him, never spoke to him. And he is gone for such a long time. Maybe he never existed. Perhaps he is dead. Doubtful people, agnostics who live in this empty house, do not know what to think. We hear the reports, the stories, and the narratives, we understand the expectation, the tradition, the customs, and the rites. We know so many families now claiming that different Gods owned the house. But we have no memory of any of those owners, and met nobody with that memory. We are not witnesses and know no witnesses. God left so long ago that we doubt he ever was present in the house in the first place. He may be just an impostor, or an old story, which people kept embellishing for centuries and then millennia, invented to shed responsibility for their lives and the house. For if the place is not yours, you may be forgiven for the frequent oversights, even the systematic neglect. You may even think that God will take care of your planet. You may even kill in the name of the right owner of the house who one day will come back. If your life depends on someone else, who can give meaning to it or destroy it, that may feel quite comforting, especially if living in the house is tough and challenging, too uncertain without God's ownership and return, too difficult to manage and accept. A great owner who is coming back is the perfect excuse for a lazy life of postponements, delays, procrastinations, delegations, and deresponsabilisations.

Many believe he does not exist. Many others that they deserved to be abandoned. Some have faith in his return. Those more doubtful, the agnostics again, may decide that the best thing to do is to live as if God will never come back, as if he were only a nice story but never existed, and take care of the house and themselves, for there is nobody else who will, while still hoping against hope (the beauty of some English phrases) that they may be wrong. They assume the worst scenario, knowing that the best, God’s return, will take care of itself. Should God ever come back, he will find them caring for his house and their well-being.

All this may sound like Pascal’s wager, but it is not. Pascal wants to cheat God. His suggestion is to assume his return and borrow from that return whatever added value may be available, which is the semantic capital that gives meaning to your life. If God never comes back, if he never existed, that borrowing will have been interest-free, and you won’t have to repay what was never yours. But if he does, you will still have borrowed interest-free, but as long as you invested wisely, you will be able to repay him. This may be smart, but it does not seem a nice way to treat the master who left, assuming he actually left. Assuming his return, banking on it, taking his money, investing it well, and being ready to give the money back, should he ever show up again: no wonder Pascal thought it was a win-win. But it seems to me a bit dishonest. Using God and his return as a means, not an end, to have a meaningful life now whose meaning is not yours but merely borrowed, not created through hard work or real commitment, but thanks to a mere calculus of what would be the most convenient strategy. Pascal’s faith is like borrowing at no cost, having no intention to pay back unless one is asked. It may work logically. People have debated whether it does for a long time. But morally, I don’t like it. Much better to operate on the opposite assumption. If in doubt, as an agnostic (and rationally you should be in doubt), act as if God will never come back and will never reward your efforts. Act as if you were alone. Act morally and meaningfully in a gratuitous way. Take care of the empty house. Make your life meaningful, do not merely assume it is meaningful just because you think it’s more useful to bet that God may be coming back. If he has left forever or was never around in the first place, you will be the master of your life and the house. There are worse things on earth. But if, against all odds, he does return, if the house really is his, as you strongly doubt yet still cannot help hopping, you will be able to welcome him as a self-made man, with presents, sound investments, and your business in order. How much more praiseworthy to say “I did the right thing, even though I assumed you would never come back”, than “I assumed you would come back, that’s why I did the right thing”. The lesson about God’s absence is not that we should wait for God to come back, or cheat by borrowing divine meaning that is not ours, but that we should create our own semantic capital that will be enjoyable in itself and our gift, should God ever come back.

So, for an agnostic like me, a meaningful life must be, as much as possible, an entirely immanent, historical, and human creation, not based on faith, or the belief in some transcendent reward. I don’t want to borrow freely, knowing that I could be rewarded for cheating, but create my own semantic capital, and in case be rewarded for not cheating. Not because I know that God is not coming back, for I do not and cannot, but because I wish to have a present if he returns after all, even if I strongly doubt it.

Contrary to what Pascal suggests, I prefer to live as if God did not exist while hoping I might be wrong.

A dear friend once told me that people in Naples have a beautiful way of saying: when you visit someone, you must knock on the door with your feet. The explanation: because your hands are full of presents. That is how we should knock on the door of the kingdom of heaven, with our arms carrying a meaningful life, as a gift we neither stole nor borrowed surreptitiously, but created and accumulated by ourselves. Strongly doubting, and yet still hoping, that someone may open the door.

PS "Notes to myself" is available as a book on Amazon: ow.ly/sGyh50KfRra

Photo by Alexander Andrews on UnsplashOnlife - Luciano Floridi's blog

On why publishing (series: notes to myself)

Why does one publish anything at all? In a world that is always distracted. That already has millions of books. That has more classics than anyone will ever be able to read. In a world that does not read, does not care, does not mind. Why, really?

Why does one publish anything at all? In a world that is always distracted. That already has millions of books. That has more classics than anyone will ever be able to read. In a world that does not read, does not care, does not mind. Why, really?If writing were just a dialogue with oneself, there would be no need to make it public. Why involve others in a private struggle? What is this need to share one's own thoughts? Something is wrong.

Let me exclude some obvious answers. Of course, there are professional requirements: an academic, for example, will struggle to get a job without publications. There may be commercial needs: hoping to make some money, or just being able to support oneself. Commitments and promises can also play a role. Ambitions of fame and hopes for glory should never be underestimated, no matter how groundless. And with them, the glimpse, or just the illusion of a slice of immortality, or at least of a less short memory. Someone may read you, one day, in the distant future.

Perhaps. But all this seems a distraction, not yet the real answer. Let's assume there is no pressure, no further reason, no heteronomy: no job, no money, no fame, no contract, no expectations, no promise, no need or reward of any kind, no nothing of the sort. Why would you make the production of your mind public, assuming that this is what publishing means? It's the same question one could ask about a rich artist or writer. Why do they care so much to make their intellectual creations public? Perhaps one wouldn't, it may be retorted. No carrot, no stick, no publishing. But I'm not convinced.

Suppose you were the last man on earth. You know you will not be read. And yet, you may still publish, so to speak (mind the qualification), your thoughts. Write them down, revise them, edit them, and make them accessible at least in theory, counterfactually, as if there were someone who could read them. People write diaries while hoping that such diaries may remain secret. They "publish" without wanting or wishing to make their thoughts public. This is not the same, but it is much closer to the publishing I have in mind. It is the unread publishing, the bringing it out into the open, but invisibly so, that seems to matter. This seems closer to answering the difficult question, but there is more.

I do not know a word to express this idea of public unreadigness. I searched, but "samizdat" will not do, it is another "almost", like a secret diary, even if for other reasons. Because the term refers to the clandestine publication of banned literature in communist countries of Eastern Europe, but that was still meant to be read by the right people. Still, "samizdat" does help a bit, by pointing towards the practice of self-publishing, as it derives from "sam" ("self, by oneself") and izdat (an abbreviation of izdatel'stvo, "publishing house"), and thus means "self-published". We are getting close.

Secret diaries, clandestine literature... can be forms of self-publishing which of course refer to the publication by an author directly, without the intermediation of a publisher. But here I like to interpret it differently, as publishing not by oneself but for oneself, no matter whether directly or indirectly, with or without the mediation of others, the publishers.

Being published is not being read, obviously. So one could seek to "self-publish" even if longing for secrecy, or not minding public unreadingness. And that, I think, it's the significant difference. For the whole point of publishing is first of all ensuring that one's own thoughts finally solidify into a permanent artefact. Distilled and deposited into a some-thing. Stratified, like living organisms now dead, into layers of words, paragraphs, sections, pages, volumes. This happens even in secrecy, even without readers. Indeed, publishing may be more successful if it is "self-publishing", because the eyes and ears of the readers, imagined by the writer, corrupt the process of writing, like clumsy and oblivious anthropologists mingling with prehistorical people, influencing their customs and behaviours. The reader must remain an invisible presence, for the writing to be authentic.

Self-publishing is a job done properly, even if nobody will ever know, and it is done better if nobody is expected to know, even if they may. In this, self-publishing as publishing for oneself is like broadcasting: the formulation and transmission of one's own thoughts, even if no one is listening, even if the universe is dead, even if you are the last man on earth.

And so, by committing your thoughts to some external support, by "self-publishing" without minding whether reading will follow, you reify your thoughts and make them external, and enable more thoughts to develop, building these new thoughts on the calcified ones now in the world. In this, self-publishing as publishing for oneself resembles the private mourning of one's own thoughts, which have completed their journey and can now rest, ultimately detached from that mind that kept them alive.

But publishing as "self-publishing" is also about liberating oneself from the mental pressure of thoughts that have become unbearable, from thoughts that are ready to be born. Any Athena gives an awful headache to her Zeus, no matter how small both divinities may be. It is about being able to use those self-published thoughts as new input for other thoughts, new explorations, enjoyable at first, soon to become painful, and later ready to be self-published themselves, in a cycle of genesis, expulsion, and leverage. A bit like the God of the Bible, who could not help having us, but needed to get rid of us to have other thoughts, apparently to save us.

And so, the answer to the question is that, ultimately, you publish because you publish for yourself, and your only good publishing is this self-publishing, so that your thoughts may be dead to you, external compost for more internal thoughts, no matter whether they may be alive to others, should they wish to welcome them.

PS "Notes to myself" is available as a book on Amazon: ow.ly/sGyh50KfRra

Photo by Giammarco Boscaro on UnsplashOnlife - Luciano Floridi's blog

Call for expressions of interest: research position for a project on Digital Sovereignty and the Governance, Ethical, Legal, and Social Implications (GELSI) of digital innovation.

Call for expressions of interest: research position for a project on Digital Sovereignty and the Governance, Ethical, Legal, and Social Implications (GELSI) of digital innovation.

Call for expressions of interest: research position for a project on Digital Sovereignty and the Governance, Ethical, Legal, and Social Implications (GELSI) of digital innovation.The Centre for Digital Ethics of the University of Bologna https://centri.unibo.it/digital-ethics/en invites expressions of interest (EOI) from early career researchers, with a relevant Master or PhD degree, interested in developing a research project in the field of Digital Sovereignty and the Governance, Ethical, Legal, and Social Implications (GELSI) of digital innovation.

The EOI should include three documents (all in English):

1. a letter (ca. 500 words), including relevant details about personal motivation, relevant skills, experience, and a link to a Google Scholar profile;

2. a short CV (max 3 pages), including a list of publications; and

3. a short (ca. 1,000 words) outline of the proposed research project about digital sovereignty and the GELSI of digital innovation, indicating: topic, methodology, deliverable, and timeline.

Deadline for the EOI: 1 June 2023.

The position is envisaged to last two years, with an initial appointment of one year renewable upon satisfactory progress. It is not expected to be residential.

Please send your complete EOI to CEDE Segreteria Amministrativa by email (also in English) to: segreteria.amministrativa.cde@gmail.com

Onlife - Luciano Floridi's blog

Between a rock and a hard place: Elon Musk's open letter and the Italian ban of Chat-GPT

Interview by Adele Sarno for HuffPost, the Italian original is here

Interview by Adele Sarno for HuffPost, the Italian original is hereThe following English translation is provided by Google, apologies for any imprecision.

Luciano Floridi, the digital philosopher, works between Oxford and Bologna, from next summer, he will leave Oxford to direct the Center for Digital Ethics at Yale. He has received the highest honour granted by the Italian Republic: Cavaliere di Gran Croce. According to the Elsevier Scopus database, he is the most cited living philosopher in the world. If today we talk about the "philosophy of information", it is thanks to him, who for 30 years, studied the connections between philosophy and the digital world.

Professor Floridi, ChatGPT has been at the centre of the debate, especially these days. Elon Musk and a thousand other experts have written a letter asking for its development to be stopped for six months. In Italy, on the other hand, the privacy guarantor has decided to stop for 20 days until it complies with the privacy regulations. What's going on?

"As soon as ChatGPT came out, the controversy started, but I suggested not to block such tools, and to teach their proper use in school. They are handy tools, flexible, powerful, and easy to use. It makes no sense to demonise them. But when there is something new, the first instinct is to stop it, waiting for something to happen. You see the problem, but you don't offer a solution."

What can happen now that the Italian Data Protection Authority has stopped the use of ChatGPT in Italy?

"It is a draconian reaction which to me seems potentially excessive because the solution should be a compromise, not a blockade. The Italian Data Protection Authority is right when it says that the service is aimed at those over 13, but the program has no real verification filters. It collects all your data when you interact with it; they inform you clearly before using it. And advertising will probably come too. Not to mention the training data and the data leaks. So there is a privacy risk, and data management is certainly not up to European standards. But introducing more serious online registration, and a more regulated use of data should be the way forward. In short, going from 'free for all, do anything' to 'blocked' seems excessive and risky. I believe that looking for other possible solutions is a must. I hope that we are working in this direction".

The Italian Data Protection Authority on HuffPost says he has nothing against progress. But innovation cannot be done at the expense of people's rights. In particular, he claims that ChatGPT is trained thanks to billions of data from billions of people, so it must be blocked.

"There are at least two main problems with doing this. The first is that ChatGPT will continue to be used, because, in this case, a VPN is all you need, and therefore an underground usage and the usual rift will be created between those who know how to do these things and those who have no idea. With consequences that reach even a deeper level: just think of the schools where it will be impossible, at least legally, to educate in the good use of this tool, of the world of research - I use GPT4 daily - or of the world of work, where for example, it is commonly used to write lines of code. Furthermore, a context is created which replaces dialogue with confrontation. Then there is the uncertainty regarding all those contexts in which systems, such as ChatGPT and other so-called Large Language Models, are already integrated into search engines, as in the case of Microsoft".

The Italian Data Protection Authority also says that the block depends on the fact that the information provided by this technology is inaccurate.

"On inadequacy, two aspects can be distinguished. On the one hand, the system errs on the side of caution because you have to work hard to make it say something bad or wrong. It's a do-gooder, doesn't even give you the recipe for horsemeat, and lectures you if you don't ask the right question about it. On the other hand, it is a statistical system, and sometimes the answers are completely unreliable or made up. I recently had to summarise my work for the usual, bureaucratic, mindless reasons, and GPT4 described me as a Belgian philosopher. At the same time, the summaries of the books were very good.".

So the block doesn't make much sense?

I don't know all the reasons that led to the decision. The effect is that Italy is now out of the development of this technology. Because I expect that, for consistency, the block should be applied to all the various similar applications produced by Google, Meta, Microsoft, and so on. But how can we curb a phenomenon that is already underway? Do we stop search engines along with ChatGPT? In a context where there is commercial competition, and where the interests are tens of billions of dollars, it is difficult to stop everything voluntarily, for fear of science fiction scenarios, as in the case of the letter, or by going through a total blockade of technology, as in Italy. Not only will no one stop. But, in the case of the letter, it is a hypocritical operation. If then one requires that the instrument, to be usable, must be infallible like a calculator, we know that it will never be, because it is neither deterministic nor controllable like a calculator. It is inherently fallible because it is based on statistical analysis done on billions of data points. If this is the reasoning, then you are asking the impossible; in fact, you are saying that this tool can never be used. It reminds me of what happened with synthetic meat in Italy [note: the production has been banned]. Instead, we should try to understand how best to regulate the use of these technologies, mind you, not the technologies themselves, but how they are used, for what purposes, what we do with them, and in which contexts. In part, European legislation is coming to this, but only in part".

Yet Musk and a thousand other GPT4 experts wrote a letter saying we are creating super-powerful digital minds.

"The letter is a bad soup of things: good and a little trivial, wrong and science fiction. That passage about super-powerful digital minds sounds like something from a bad Hollywood script. It disinforms and scares, distracting from the real issues. A bit like raising the alarm for the possible arrival of zombies.".

Yet it was signed by over a thousand experts in the AI sector.

"It's as if we had a rope with many strands. One is that of disinformation. Another is that of mass media fame and prominence as an influencer. Then there are the naive, those who want to feel part of a community, those who think it's better than nothing, those who believe that zombies are coming, those who have good intentions and click on "sign here" without thinking twice, following the flock, those who want to shift attention to technology and not to those who produce or use it, those who wish to promote self-regulation and postpone the arrival of legislation. I certainly won't sign it. A single rope is created from all these strands that drags the same effects: alarmism about the wrong things, scientific disinformation, protagonism, and public distraction. Two small examples: there is no reference to all the significant legislative developments on AI, not only in Europe but also in America, or to the environmental impact of these technologies. And it is omitted that we have been recommending self-regulation for a decade, without any effect, remaining unheard of precisely by the producers of the AI in question and by some promoters of the letter, such as Elon Musk. In the rope, there is, therefore, also a strand called hypocrisy.

He talked about it several times on HuffPost. The infosphere is still a new place in the common imagination and is based on the circulation of information, here whoever controls the information has the keys to everything. Isn't there a risk that in the absence of clear rules, the same mistake that the Clinton administration made 30 years ago will still be made? Leave such fundamental decisions to the big Big Tech companies of Silicon Valley, and somehow delegate everything to self-regulation?

"I don't know if this is the end of the letter. But that's the risk we run. As I was saying, there are many strands in the rope, and the reasons that hold them together are different, but together these strands deliver something. And I fear that this something is delaying legislation, a further attempt at self-regulation, a mass distraction on problems that are not the real ones, namely manipulation, disinformation, the extraordinary power of control of the producers of these tools over who uses them, and then the misuse by those who ordinarily deploy these tools for immoral or illegal purposes, just think of organised crime or regime propaganda. All of this is without mentioning the environmental impact, which is very significant. It is sensational to shift the attention and blame for everything on generative and non-generative artificial intelligence, when actually the real problems are upstream, with those who produce it, and downstream, with those who use it badly and hence with their misuse. I fear that there is bad faith in those who lead this operation, and a lot of naivety in those who have joined the queue".

Let's talk about legislation, a fundamental element that unites the provision of the Guarantor and the letter. Where are we?

"ChatGPT is a great tool, and one needs to know how to use it well. But above all, we need to understand how to manage it from a regulatory point of view. European legislation is on the way, with the AI Act. It can be criticised and improved, but it is a good step in the right direction. However, it has a fundamental problem: it focuses on artificial intelligence as if it were a product whose safety must be guaranteed, imagine a microwave oven, and not on its use and applications, which can be benevolent, or malevolent and highly risky. But AI is not an artefact or a product; it is a service, i.e., a form of agency, an ability to carry out tasks or solve problems. For this reason, now is the time to understand what regulatory framework must be designed for this technological innovation. There is still time to regulate its uses, straighten the course, and work on the "how" and not the "what".

So, without a clear regulatory framework, did the Italian Data Protection Authority appeal to the GDPR?

"The Italian Data Protection Authority has requested Open AI to comply with the GDPR. But if we are asking – and I emphasise the if – that these systems must, for example, obtain permission to use all public web pages written in Italian to learn how to interact in Italian, and that they must then always be correct when they provide the requested information from an Italian user, then we are asking for the impossible. It seems to me that the regulatory framework is not adequate, because the only thing that can be done with it is to ban it. A bit like using the legislation on carriages to apply it to cars. But history teaches us, prohibition is useless: it's like blocking the sea with a colander. This is why I hope that the initial "if" is just my interpretative error".

Much ado about something that someone has compared to a parrot.

"No, no, a parrot is much smarter. GPT4 is much more like a "linguistic calculator", shall we say. It is a syntactic calculator, which treats natural language as if it were mathematics: it doesn't memorise and repeat a solution, it creates it. The question is not what answers it can give, but what you do with those answers. Plato already said it: the expert is the one who, above all, knows how to ask the right questions. It is better to understand how to use and teach it, than to ban it. It seems to me that the arrival of these tools actually purifies the true essence of human intelligence, because it detaches it from any form of encyclopedism, the ability to remember a thousand facts, and mere erudition. It is the question, and the purpose of the question that makes the difference.".

Is there a risk, especially in the absence of legislation, that our social networks are literally overwhelmed by fake news and deepfakes?

"It is a severe danger, which is also briefly indicated in the letter, one of the few good things about that text: we run the risk of deep and serious pollution, especially on social media. This can be summed up in two words: disinformation and manipulation. For those who want to perpetrate both, such powerful tools, which create and manage any content, language, image, sound, or video, are ideal. They allow for industrial processing. This problem is serious. The solution is: more and better legislation, as soon as possible. No sci-fi worries or Draconian blocks".

Onlife - Luciano Floridi's blog

On pale colours (series: notes to myself)

.jpg) Pale colours are the hues of discrete affluence. Often green or brown, sometimes blue, less frequently red, all deeply tinted with white, greyshed and matted, they speak of detached lives and tastefully expensive houses.

Pale colours are the hues of discrete affluence. Often green or brown, sometimes blue, less frequently red, all deeply tinted with white, greyshed and matted, they speak of detached lives and tastefully expensive houses.They match the oaky, automatic gate; the spacious, walled gardens; the grass, carefully mowed by invisible others; the roses, hobbily attended by the well-mannered owners; the expensive, conscientious electric cars in the courtyard; the old carpets to warm the creamy, stony floors; the terracotta in the spacious kitchen; the solid, timbered ceilings; the wooden doors; the immaculate linen; the bathrooms' ivory basins.

Pale colours are quiet and unobstructive. They wish to be old, like unembarrassing money. Even when recently painted, they pretend to have been washed by centuries of tradition, smoothed by classic virtues and family reunions. They are meant to smell like musky wealth that does not age but accrues, of private schools for the children, of Oxbridge sports, of a library with forgotten ex libris, of old and silveryframed pictures next to the accomplished piano, of graphite fireplaces that never stopped working, of waxed furniture inherited with the crystal glasses and the silver spoons, of ancestors' jewellery, of paintings whose collectors have been forgotten.

Pale colours bridge generations. They want to be educated not merely acculturated, refined not sophisticated, stylish not fashionable. They are soft and unchanging, smoothed to hide the corrosion of time, polished to pretend never to be eroded. They whisper stories of continuity, solidity, stability, permanence.

And as I walk, and I see them around me, I know they are just a layer of discreteness on the indecent caducity of the objects they cover, a grey and pudic veil that seeks to hide the world from violent loudness and aggressive change.

I cannot help it. I like them. But I know I should cover my eyes like Odysseus his ears, because they are lying.

PS "Notes to myself" is available as a book on Amazon: ow.ly/sGyh50KfRra

Onlife - Luciano Floridi's blog

Elly Schlein: otto motivi per sperare, otto motivi per temere

Qui il testo originale pubblicato sull'HuffPost

Qui il testo originale pubblicato sull'HuffPostElly Schlein: otto motivi per sperare, otto motivi per temereUn vantaggio dell’essere lontano dall’Italia è quello di poterla “vedere da lontano”. Ovviamente il rischio è di prendere abbagli e fischi per fiaschi, ma forse si riescono a vedere meglio le cose, con più distacco e in prospettiva. Sperando che quest’ultimo sia il caso in questione, ecco un breve commento su come appare l’elezione di Elly Schlein come Segretaria del Pd.

È un evento importante. Prima donna al comando del Pd, e altra donna di spicco, in una politica sempre più personalizzata, Elly Schlein è l’alternativa a Giorgia Meloni. E per questa alternativa, a leggere e sentire le varie opinioni, mi pare che si presentino due scenari, due linee di sviluppo all’interno delle quali si collocano gli altri scenari misti, insomma il bianco e il nero da cui nasceranno i vari grigi. Dal punto di vista di quelli che hanno votato, li chiamerei Speranza e Timore, un po’ Jane Austen, un po’ Fëdor Dostoevskij. E siccome non c’è spazio, li delineo in pochi punti più facilmente criticabili da chi non sarà d’accordo.

A) SPERANZA (basata sui 12 punti del programma di Schlein)

- Il Pd si rinnova, liberandosi della sua casta interna e delle varie correnti, e facendosi portatore di una politica da 21° secolo, puntando sulla maggiore partecipazione della società civile, sull’apertura all’immigrazione e alla cittadinanza allargata, sulla difesa e l’implementazione di diritti e doveri civili, sulla promozione di riforme profonde, e anche inizialmente impopolari per gl’interessi costituiti, al fine di svecchiare e dinamicizzare il paese, sull’investimento nel digitale, nella formazione, nel lavoro, nella sostenibilità, nell’innovazione tecnologica, e nella crescita economica, sull’adozione di una solidarietà diffusa, su più presenza nell’Ue, sul sostegno all’Ucraina e alla Nato, etc.; in tal modo...

- il Pd, pur perdendo voti di protesta, populisti e d’interesse, assorbe molti voti sia dal centro, indebolendo Calenda-Renzi, sia dal M5S, portando quest’ultimo verso posizioni più costruttive e meno demagogiche o di mera protesta e rivendicazioni, pur di contare e non restare isolato, creando così...

- una rinnovata fiducia in una politica alternativa al centro-destra, di stile lib-dem o Labour (ma non quello di Jeremy Corbyn), con una identità chiara e incisiva, che dà fiducia in termini di competenza e rigore, anche economici, e che riesce ad...

- attrarre gli indecisi, i non-votanti, i neo-votanti, chi si astiene in modo programmatico, chi ha sempre la tentazione di non votare, ma soprattutto chi dalla politica vorrebbe meno ideologia e più soluzioni concrete (sul che cosa) e fattibili (sul come), disegnate da un partito che fa opposizione costruttiva mentre si prepara a governare; questa nuova attrattività porta...

- alla vittoria del Pd + M5s + alleanze alle prossime elezioni, con il Pd come partito di governo, quindi...

- alla riduzione dell’importanza dei partiti di centro, alleati del, o assorbiti dal Pd, irrilevanti o non più esistenti, mostrando che il termine “centro” in centro-sinistra ha altrettanto peso e valore quanto “sinistra”, e...

- alla frammentazione del centro-destra (venendo meno l’interesse emergono le differenze e i dissensi) e alla migrazione di alcune sue parti, più liberali e solidali, verso accordi ad hoc con un Pd + M5s+ alleanze al governo, in conclusione...

- (abbiamo dieci dita, diciamo quindi che) si va verso un decennio di centro-sinistra come forza nazionale, e non solo regionale.

- Pd e M5s si avvicineranno ma, assumendo che l'alleanza riesca, l’unione-alleanza-intesa non sarà un partito progressista/riformista, diciamo una sorta di nuovo lib-dem, ma un centro-sinistra un po’ indifferenziato, populista e di protesta, più movimento di denuncia e indignazione che piattaforma progettuale, con il rischio ulteriore della M5s-ificazione del Pd; ne segue che...

- ci saranno troppe operazioni da centro-sinistra intellettuale – casta e correnti varie saranno ancora influenti – e poca concretezza sul come rimettere a posto il paese, si parlerà tanto di diritti e poco di doveri, tanto di assistenzialismo e supporto e poco di crescita e investimenti, molto di lavoratori e poco di datori di lavoro, mentre riforme serie o politiche lungimiranti – che costano in popolarità – non saranno pop e quindi non verranno elaborate nel dettaglio, ma solo accennate a grandi linee, insomma si cercherà di recuperare consenso, cavalcando malcontento, rivendicazioni ottimistiche, mode, proteste, aspirazioni idealistiche e promesse utopistiche più che disegnando serie proposte di buon governo, competenti, e fattibili, che risolvono i problemi passati, riformando il presente, e affrontano quelli futuri con una gestione costruttiva del progresso per il benessere di tutti e dell’ambiente; anche per questo...

- il Pd sarà percepito come un partito di opposizione ma non di governo da tutti quelli già elencati nel punto (4) sopra; il voto al Pd sarà visto come un voto perso, o di protesta, e tutto ciò metterà in crisi la natura unitaria del Pd, già molto fragile; quindi...

- il Pd vedrà una ulteriore emorragia di voti dei delusi (per esempio gli iscritti che si aspettavano un netta vittoria di Stefano Bonaccini), degli stanchi, di quelli che sono più di centro che di sinistra o che appartengono al mondo cattolico, o ad altre correnti più vicine a politiche liberali (emorragia verso Renzi+Calenda), o che sono più populisti che di sinistra (emorragia verso M5S), per non parlare di coloro che smetteranno di (o non inizieranno neppure a) votare qualsiasi partito, Pd incluso; anche per questo si arriverà a...

- una probabile scissione del Pd (non avverrà subito ma con i tempi definiti dal bon ton della politica); questa renderà...

- il centro-sinistra più debole, frammentato, meno centro e più sinistra, e un centro riformista/progressista con un ipotetico triumvirato Bonaccini-Calenda-Renzi (NB i nomi non contano, potrebbero cambiare nei prossimi anni, portando anche a fusioni) leggermente meno minoritario, e potenzialmente “king maker”, cioè ago della bilancia, almeno nelle velleità, non tanto nel decidere chi va al governo (una simile coalizione con il centro destra sembra improbabile) ma soprattutto nell’influenzare quale legislazione e quali politiche verranno implementate con alleanze ad hoc, e quale “cultura politica” di centro-destra/centro e aspettative sociali e economiche domineranno nel paese; in questo caso...

- un centro minoritario ma leggermente più influente potrebbe portare più facilmente il centro-destra a spostarsi verso posizioni più centriste-riformiste e meno reazionarie e conservatrici, mentre è improbabile che centro e centro-sinistra trovino un accordo; visto tutto questo...

- (sempre con le stesse dieci dita) si va verso un decennio di permanenza della destra o del centro-destra al potere, con un Pd indebolito e cronicamente all’opposizione e un M5s privo di una reale filosofia politica e chiari criteri che differenzino i due partiti, se non diverse enfasi su rivendicazioni, denunce, e forme di assistenzialismo (oltre alle ovvie strutture di potere, segreterie, etc.).

A e B sono frutto di un po’ di analisi logica, niente determinismo e niente fatalismo, solo due ipotesi, in cui ogni punto potrebbe essere errato non solo in parte, ma anche del tutto, e ribaltato completamente, o mescolato per ipotesi alternative meno polarizzate. La storia è imprevedibile, ma se dovessi puntare, purtroppo punterei sulla realizzazione del timore e non della speranza.Spero di sbagliarmi. Ma soprattutto sono felice di non dover puntare.Onlife - Luciano Floridi's blog

Call for Papers for American Philosophical Quarterly’s special issue on The Ethics of Artificial Intelligence

Call for Papers for American Philosophical Quarterly’s special issue on The Ethics of Artificial Intelligence

Editor in chief: Patrick Grim

Guest editor: Luciano Floridi

Artificial Intelligence (AI), from machine learning to robotics, generates enormous opportunities and significant challenges. In the past few years, many of them have led to a flourishing of international initiatives and growing research concerning the ethics and governance of AI. This special issue solicits the submission of original articles that investigate how AI is transforming classic questions or leading to new ones in moral thinking, and how such questions may be addressed successfully. Topics of special interest include but are not limited to AI and: authenticity, creativity, and intellectual property rights; bias, discrimination and fairness; the digital divide; digital sovereignty; capabilities and empowerment; cyberconflicts and cybersecurity; fake news and deep fakes; ethical frameworks and principles; ethics-base auditing; human autonomy and self-determination; sustainability and sustainable development goals.

All approaches, methodologies, and schools of thought are welcome, with particular attention to sound and evidence-based reasoning. Purely historical or speculative articles are not encouraged.

To submit a paper for this special issue, authors should send an email to

Elisabetta Bulla, Centre for Digital Ethics, University of Bologna

segreteria.amministrativa.cde@gmail.com

including name, surname, academic affiliation and preferred email in the body of the email and the submitted article, fully anonymised, in word format, as an attachment.

The deadline is 31st of July 2023.Onlife - Luciano Floridi's blog

Futuro Antico. Intervista al filosofo Luciano Floridi By Marco Bassan -11 Gennaio 2023 per Arttribune

Condivido la versione corretta dell'intervista uscita su Arttribune. Purtroppo la versione pubblicata per errore è la prima bozza.

Condivido la versione corretta dell'intervista uscita su Arttribune. Purtroppo la versione pubblicata per errore è la prima bozza.LA FILOSOFIA DELL’INFORMAZIONE, LA FILOSOFIA DELL’INFORMATICA E L’ETICA INFORMATICA SONO I CAMPI DI INDAGINE DI LUCIANO FLORIDI, AL QUALE ABBIAMO CHIESTO DI RIFLETTERE SUL DOMANI

Il filosofo Luciano Floridi (Roma, 1964), naturalizzato britannico, è professore ordinario di Filosofia ed etica dell’informazione presso l’Oxford Internet Institute dell’Università di Oxford. È anche professore di Sociologia della comunicazione presso l’Università di Bologna, dove dirige il Center for Digital Ethics.

Dall’arte agli auspici (e ai timori) per il domani, ecco una sintesi del pensiero di Floridi.

Quali sono i tuoi riferimenti ispirazionali nell’arte?

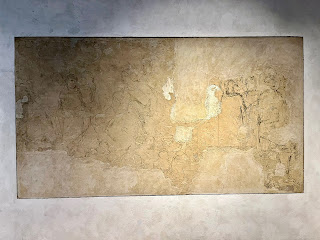

Evitando i grandi classici come Raffaello, Michelangelo e Caravaggio l’arte contemporanea che trovo più vicina a me, anche filosoficamente, e da cui traggo ispirazione è la Land Art. Ho come la sensazione che forse sia avvenuta troppo presto e si sia consumata in un periodo in cui non la si è capita abbastanza e oggi sia talmente scontata che abbia superato il suo momento di rottura e quindi non sia più di moda. È partita così tanto in anticipo e in un momento in cui la nostra comprensione per l’ambiente non era così raffinata che credo che se si sviluppasse oggi sarebbe dirompente. Per Land Art non intendo solamente le installazioni in natura di Richard Long ma anche l’arte urbana che racconta un modo di vivere l’habitat che è sensibile nei confronti degli aspetti più estetici della nostra esistenza. Infine, un’opera che di recente mi ha colpito particolarmente sono le sinopie degli affreschi di Mezzaratta nella Pinacoteca di Bologna [LF: vedi immagine sopra in questo blog]. Le figure vagamente accennate, quasi etere di questi disegni preparatori, rimossi da una chiesa ed esposti nella pinacoteca, hanno un aspetto estraneamente contemporaneo che tracciano a mio parere con la Land Art un filo rosso in cui l’umano si fonde con il naturale e con l’ambiente.

Quale progetto ti rappresenta di più? Puoi raccontarci la sua genesi?

Dal punto di vista biografico, quasi intimistico, è um libricino che ho realizzato recentemente che si chiama Notes to myself - Notes wrapped around a bottle with a rubber band (la copertina è un dettaglio delle sinopie di cui parlavo). Il sottotitolo prende ispirazione dal libro di John Steinbeck, Viaggio con Charley, in cui ad un certo punto parla di alcune note che ha messo insieme nel corso di quel viaggio, in cui descrive un’America che sta sparendo: "And I made some notes on a sheet of yellow paper on the nature and quality of being alone. These notes would in the normal course of events have been lost as notes are always lost, but these particular notes turned up long afterward wrapped around a bottle of ketchup and secured with a rubber band.” Questo mio libro è una selezione di note che raccolgo in un blog e che ho deciso di pubblicare su Amazon al prezzo più basso possibile per il cartaceo e gratuito in formato digitale. Mi piacerebbe aggiornare l’edizione regolarmente, con nuove note. Sono note brevi, non strettamente collegate, idee per libri che non scriverò mai, ricordi che mi hanno formato. Sono note non fatte per apparire in un certo modo, ma solo per raccontare le tante cose che passano per la testa e che probabilmente non andranno mai da nessuna parte. Scrivendole riesco a sgombrarmi la testa da esse. Lo diceva bene Gilbert Ryle che pubblicava testi proprio per toglierseli dalla testa, per fare un dumping di idee. Ovviamente queste note nel libro sono curate, ma, come per la barchetta di carta lasciata andare sul fiume, la cura è un modo per liberarsi di queste idee.

Quale è l’importanza per te del Genius Loci nel tuo lavoro?

È fondamentale, e paradossalmente avrei una risposta duplice: esiste un Genius Loci esterno e uno interno.

Grazie a mia moglie, che è il vero genio della famiglia, ho capito che ho un Genius Loci agostiniano, interno, uno spazio mentale al quale accedo con una facilità impressionante ovunque io sono. Mi assento mentalmente senza difficoltà. Agostino diceva: “Noli foras ire. Non uscire fuori, la verità abita al tuo interno" e questa frase, che rimane famosa nella storia della filosofia, viene anche ripresa da Rilke in Lettere a un giovane poeta. Questo interno è il mio Genius Loci agostiniano.

Il secondo Genius Loci è rappresentato dagli spazi in cui lavoro. Abbiamo scelto apposta una casa bellissima, una vecchia fattoria ristrutturata nella campagna inglese, con grandi spazi e un immenso silenzio. In questo caso il Genius Loci è un po’ bucolico e anche qui si può rintracciare la mia passione per la Land Art. Non ho un senso della natura come qualcosa di immacolato, genuino o primordiale. Per me la natura è in realtà un concetto culturale, una produzione della nostra concettualizzazione del mondo e del nostro esperirlo. In ogni differente cultura ciò che è naturale è differente, basti pensare alla promiscuità sessuale dei greci che con il cristianesimo diventa innaturale, o la naturalità di un giardino fatto solo di pietre e ghiaia. L’idea è che la natura è un prodotto concettuale e questa campagna inglese in cui vivo non ha niente di intoccato: ogni filo d’erba è stato curato da generazione, ogni albero è stato potato, ogni rosa è stata importata, ogni pietra è stata spostata… però questa cura ci da un senso di abitabilità di uno spazio che è consono alla cultura interna.

Infine, l’altro Genius Loci esterno è Guarcino, un paesino in provincia di Frosinone dove abbiamo una casa che appartiene alla mia famiglia da secoli e che per me rappresenta le mie radici. La mia famiglia ha vissuto a Guarcino sin dalle crociate e lì c’è la tomba di famiglia. È da quando ho cinque anni che mio padre mi ricorda che sarò seppellito lì, entrando a destra.

Quanto è importante il passato per immaginare e costruire il futuro

È assolutamente fondamentale ma deve essere fatto in maniera nietzschiana, liberandoci da esso. Nel testo Sull'utilità e il danno della storia per la vita Nietzsche ci mostra quanto la storia possa essere un fattore completamente bloccante. Se tu sai troppo del passato la tua capacità di innovazione è paralizzata. Qui ad Oxford, come in ogni università, gli studenti si dispongono su una curva gaussiana, a quelli più bravi, che si trovano completamente a destra della gaussiana, la prima cosa che raccomando è di smettere di leggere, prendere carta e penna e cominciare a pensare, togliersi da davanti agli occhi la luce accecante dei grandi maestri, rimanere nella penombra, farsi qualche idea propria, e armarsi di quelle idee per affrontare, il pensiero altrui, la tradizione scientifica, umanistica e culturale in cui si lavora, il passato, in poche parole la storia. La storia è fondamentale ma come secondo momento dialettico, è ciò con cui dobbiamo confrontarci ma non deve essere il punto di partenza, non ci deve fronteggiare, se si parte dalla storia quasi sempre ci si rimane invischiati. Il progresso si fa in seconda battuta confrontandosi con la storia, ma in prima battuta pensando qualcosa di nuovo. Prima arrivano le idee e poi il riscontro con la storia.

La cultura italiana ha grandi difficolta a scardinarsi dalla storia e per questo rischia di essere ingessata, e quando arrivano delle reazioni, come quella dei futuristi, sono spesso di strappo poiché si sente la necessità violenta di reagire a quella che sarebbe una presenza soverchiante. Chi invece riesce a confrontarsi in seconda battuta con la storia lo può fare senza bisogno di quella violenza iniziale. L’innovazione non è necessariamente rivoluzione, ma può essere una evoluzione sulla base di un rapporto dialettico. Faccio un esempio fuori dal mondo artistico. Pensiamo a Adriano Olivetti. La storia di un uomo geniale e di una straordinaria azienda può diventare soffocante. Celebrando e musealizzando Olivetti andremmo esattamente in direzione opposta a ciò che lui ha fatto, e invece di seguire la sua lezione, di costruire qualcosa a latere e poi confrontarsi con la tradizione, rischieremmo di fare di lui un riferimento mummificato, che può essere solo ammirato. Sarebbe il modo peggiore di celebrare la memoria di un genio che ha fatto esattamente il contrario. Questo succede sempre con tutti i grandi innovatori che abbiamo avuto in Italia, li si mette sull’altare e poi si cominciamo ad accendere le candeline. La filosofia moderna la facciamo partire con Cartesio che è un ingegnere militare e la filosofia la contemporanea la facciamo partire con Wittgenstein che è un ingegnere aeronautico. Loro facevano filosofia venendo non da anni di studi di filosofia medievale né venendo da anni di studi di filosofia moderna ma arrivando a latere con le loro idee che confrontano poi con la storia e la tradizione in seconda battuta.

Che consiglio daresti ad un giovane che vuole intraprendere la tua strada?

Caute ambizioni.

L’esempio perfetto si trova nell’alpinismo, anche se parlo da dilettante. Pensate all’ambizione di voler scalare la vetta più alta che riuscite ad immaginare ma con la cautela di chi fa un passo dopo l’altro, e che in montagna c’è stato e ne conosce i rischi. A volte consigliamo troppa cautela o troppa ambizione ma la combinazione tra le due per me è l’approccio giusto. Mete ambiziose, grande cautela nella metodologia e nella preparazione preparazione.

Abbiate il coraggio di avere grandi ambizioni ma anche la cautela di misurare i passi per arrivarci. E quello è un grande lavoro. L’ambizione è qualcosa di buono se alimentata dallo sforzo necessario per soddisfarla.

E poi pensare con la propria testa, iniziare sempre ogni volta con la volontà interna di chiedersi: che cosa voglio fare? Chi voglio essere? E solo dopo confrontarsi con che cosa il mondo vorrebbe farci fare, vorrebbe che fossimo.

In un’epoca di post verità il concetto di sacro ha ancora importanza e forza?